by Shane L. Larson

In a 2012 article in Esquire, the inimitable American magician Teller noted, “Sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.”

This past week, the world was greeted with the news that a worldwide collaboration of scientists, in a multiple collaborations, made a magical announcement: they have detected a faint gravitational hum coming from the Cosmos, created by pairs of super-massive black holes, strewn across the Universe, dancing around each other in slow, languorous orbits that shed gravitational waves.

An artistic interpretation of an array of pulsars immersed in gravitational waves from a distant supermassive black hole binary. [Image: Aurore Simonnet/NANOGrav Collaboration]

Like most newsflashes from the frontiers of science, the announcement is a magical moment, instilling deep wonder and inspiring an endless barrage of questions about what it means, how was it found, what does it tell us about other mysteries of the Cosmos, and why does it matter to us down here on Earth? The magic and the wonderment stem from the bigger than life nature of the discovery, far removed from the trials and tribulations of day-to-day existence on Earth — a reminder that we are part of something far larger than ourselves. But for the scientists around the world who made the discovery, it’s what Teller said:

the discovery is the culmination of decades of work, the result of spending more time on this particular mystery of the Cosmos than anyone else.

Let me tell you three things about this remarkable achievement.

[1] What is a “nanohertz gravitational wave background”?

This tale begins with the idea that nothing in the Universe has to only be found leading solitary monastic lives, drifting along in the vast void. Very often, objects can find each other (or are born together) through their mutual gravitational attraction — this includes, stars, planets, asteroids, galaxies, and as it turns out, black holes.

We know from long, detailed studies of the sky with telescopes two remarkable things.

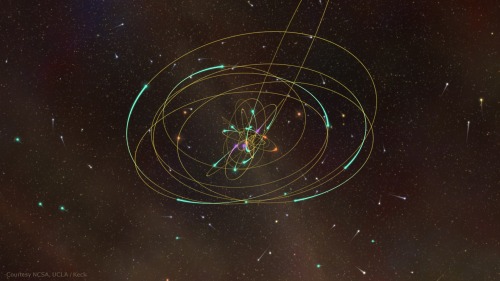

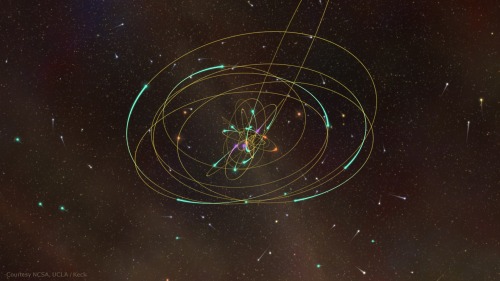

Two decades of observations have shown the orbits of stars around the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Observations like these earned Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel their share of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics. [NCSA/UCLA/Keck]

First, we know that

most galaxies have at their hearts a massive black hole, millions or billions of times more massive than a single star. If you are a science fan, you’ve heard a lot about this recently, from the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics awarded for precise measurements of the enormous black hole at the center of the Milky Way. You have likely also heard of a remarkable picture taken by the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, showing the silhouette of a massive black hole in the galaxy M87, an inky void against the glowing light of the gas that surrounds and feeds it.

The first picture of the black hole at the heart of M87, formed by light being bent around the inner most regions of space outside the black hole. [Image: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration]

Second, we know that

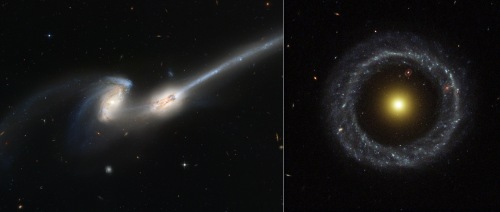

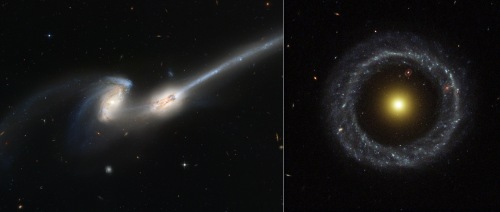

galaxies collide. One of the most spectacular examples of this are a pair of galaxies known as “The Mice,” slowly tearing one another apart as they merge over the course of a billion years. Another example is a remarkable ring galaxy known as Hoag’s Object, the result of a small galaxy dropping through the heart of a larger companion and leaving a beautiful geometry in place, like the spreading ring from a stone dropped in a pond.

Examples of the consequences of galaxy collisions. (left) A pair of galaxies mid-collision, known as “The Mice”. (right) A ring galaxy known as Hoag’s Object. [Both Images: Hubble/STScI/AURA]

These two bits of knowledge

leads to a lovely question:

what happens to the massive black holes in a galaxy when two galaxies merge and combine? The expectation has long been that the black holes would slowly sink to the center of the new combined galaxy, eventually find one another, and merge to become a newer, bigger black hole. That process of finding one another and slowly spiraling together to become one takes a long time.

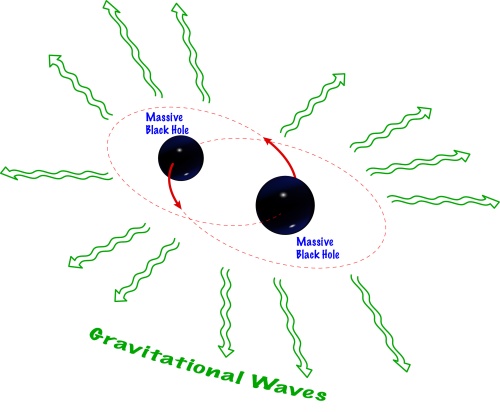

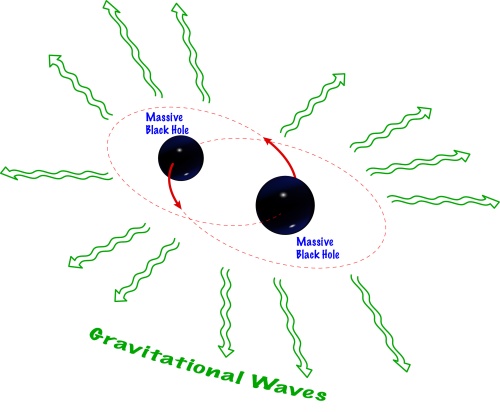

When the black holes do find one another, they dance around in an orbit, not unlike the orbits of the Moon around the Earth. Long before the black holes make their final crash, those orbits are large and can take many decades to complete. During this time, as they warily spiral around one another, they are constantly changing the parts of the Universe they are bending with their gravity, and that change ripples out through the Cosmos as “gravitational-waves.”

As massive objects orbit one another and get closer and closer together, they emit gravitational waves in all directions. [Image: S. Larson]

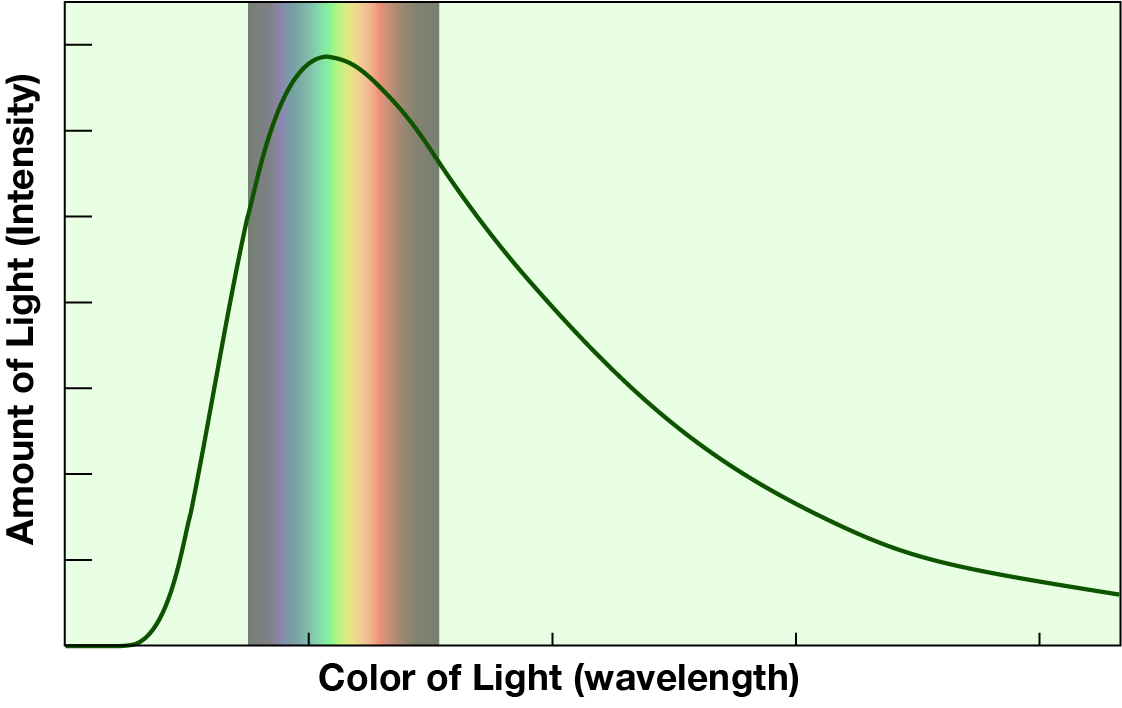

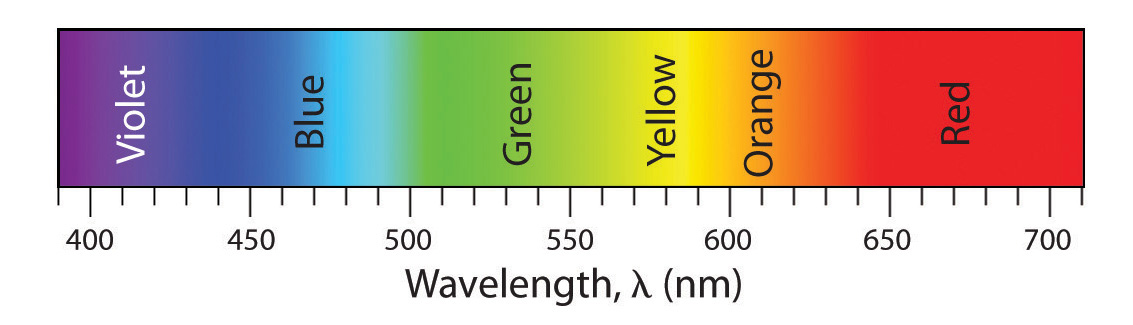

Sitting where you and I are sitting in the Cosmos, the gravitational-waves from any one of these black holes will wash through our galaxy, but only one complete wave from the black holes will pass over the course of many years. There are about a billion seconds of time that elapse every 30-ish years; if a complete gravitational wave takes 30 years to pass by, then each second means one-one-billionth of a gravitational wave passes by. Scientists abbreviate the amount of “

one-one-billionth” with the word “

nano-” which comes from ancient Greek meaning “

very small.” Nanohertz gravitational waves are waves so large it takes several decades for them to pass by.

Which brings us to the last word, “background.” This is a bit of scientific jargon, but it describes a phenomena that most of us are likely familiar with. Consider the last time you were out shopping, or at a high-school basketball game, or in a crowded restaurant. Immersed in a crowd of hundreds of people all carrying on conversations and laughing, you were immersed in a cacophony of sound. You could certainly hear the person next to you (with whom you were probably discussing the discovery of the nanohertz gravitational-wave background), but all the other conversations are overlapping and blended into the “background.” The gravitational-wave background is the same way — there are so many pairs of massive black holes strewn across the Cosmos, all of them shedding gravitational waves, that the cacophony of them merges to form a faint hum of indistinguishable signals.

From dark sites far from cities, you can see the Milky Way in the night sky overhead, as in this image over the Pando Forest in Utah. [Image: Shane L. Larson]

This idea of overlapping indistinguishable signals becoming a faint, detectable signature of the Universe is not unknown in astronomy. If you have ever had the good fortune to go camping, far from the glaring lights of our cities, and looked up to see the vast tapestry of the sky over you, you’ve likely seen the river of the Milky Way, arching overhead from one side of the sky to the other. A faint, gossamer glow of light that when you first see it may have reminded you of clouds or fog. But it is no such thing — the Milky Way is the combination of the light of a hundred billion stars in our home galaxy, each too faint to see individually, but together they make a faint light your eye can detect. The gravitational wave background is the same idea, just with gravitational waves instead of light.

[2] How was the nanohertz background detected?

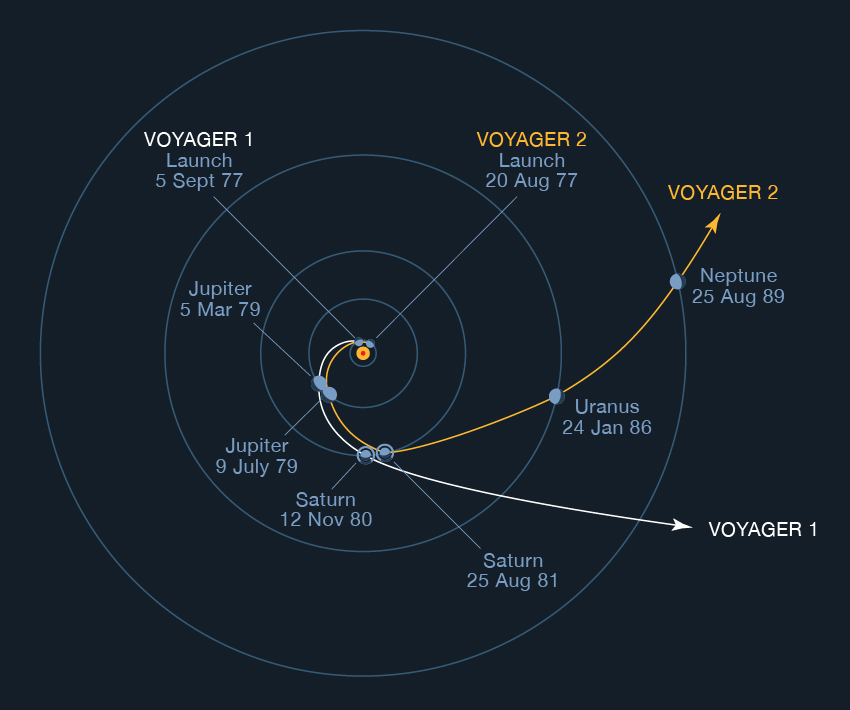

You may have heard of gravitational-wave observatories before (LIGO, and LISA), but this new discovery was made with a remarkable technique known as pulsar timing, where we mesh our own modern technology with natural phenomena from Nature to create a galaxy-spanning gravitational-wave antenna array.

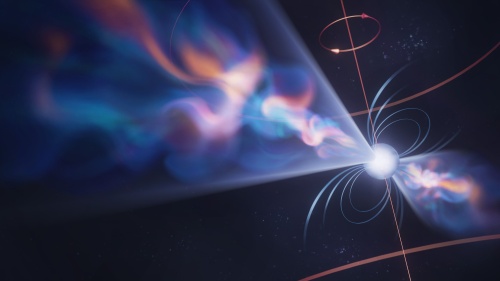

Artist’s rendering of a pulsar – a rapidly rotating neutron star that emits a beam of radio light that passes the Earth once every rotation. This results in a detectable pulse from the star, hence the term pulsar. [Image: Olena Shmahalo/NANOgrav]

It begins with dead stars — stellar skeletons of a particular type called a

pulsar. Certain stars, when they reach the end of their lives, explode and leave behind a cinder of their former selves, roughly the size of a city (about 20 kilometers across), but containing the mass of about one-and-a-half times that of our own Sun. Like most things in Nature, these stellar skeletons are rotating. What makes a pulsar “

pulse” is it has a very bright beam of radio light it is spewing out of a point on its surface — as it spins, it sweeps that radio beam across the sky, and everyone in the right place sees a bright pulse as the beam goes by, and then nothing, and then a bright pulse, and then nothing — a cosmic lighthouse jetting its signal across the Universe.

Astronomers create pulsar timing arrays (PTAs) by using radio telescopes on Earth to monitor a large collection of pulsars every now and then for decades. Today, there are several such collaborative enterprises on Earth: NANOgrav in North America, the European PTA in Europe, the Indian PTA in India, the Parkes PTA in Australia, and an overarching global collaboration called the International PTA. Each of these collaborations watches their set of pulsars, and records with exquisite precision what time each of the pulses arrives at Earth.

Because each of the pulsars lived their own lives, in their own little corner of the galaxy, we expect there to be nothing about any of the pulsars that is related between them — in the absence of anything going on, each their signals arrive at Earth at a predicted time defined by the pulsar and where it is relative to Earth. Nothing is correlated (in the literal sense of the word) between the pulsar signals.

An artist’s impression of a pulsar timing array, immersed in a sea of gravitational waves from supermassive black hole binaries outside the galaxy. [Image: Shanika Galaudage]

However, if you are timing many different pulsars, and a gravitational-wave passes through the galaxy, then a subtle pattern emerges. When a gravitational-wave passes between you and a pulsar, it stretches the distance and then it compresses the distance as the wave passes by.

When the distance stretches, it takes longer for the pulsar signal to travel to Earth, and in your timing the pulses seem to arrive late.

When the distance compresses, it takes less time for the pulsar signal to arrive at Earth, and in your timing the pulses seem to arrive early. But the magic is this: the gravitational-waves are passing through the Milky Way, and changing the spacetime between us and

every single pulsar being timed! That means before, where nothing was expected, there is now a

unique and detectable correlation between all the pulsars in the timing array!

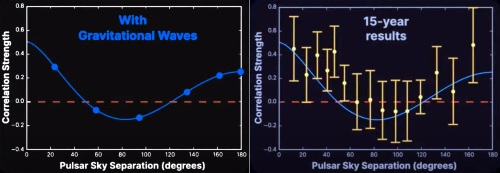

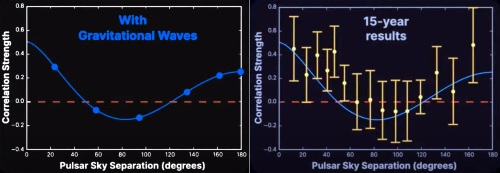

Summary graphs of the results from NANOgrav. The curve shows the correlations between pulsars in the array due to gravitational waves. (left) The red dashed line is how “uncorrelated data” from pulsars looks. The blue curve is the expected relation between pulsars when gravitational-waves pass by, known as a “Hellings-Downs curve.” (right) The same curve, with NANOgrav’s data overlaid. [Image: NANOgrav]

How long does it take for all these changes to happen and be noticed? The time it takes the gravitational wave to pass, which for the super-massive black holes can be many, many years. Which is why it has taken so long for astronomers to diligently time and retime all the pulsars in the array, and extract the ephemeral signal of the gravitational-wave background from the data.

[3] It’s really about people.

Science is often a long game, particularly science that probes the limits of human knowledge, and science done with advanced technology and tools that can’t fit in your pocket or on a laboratory bench. It takes hundreds and thousands of minds to conceive of what is possible, and then unflagging tenacity to solve each of the problems that arises until — in the end — a remarkable discovery is made. That long and arduous process means that people come and go, as they follow their own winding pathways to careers and life. But it also means we lose some people along the way who pass on, returning to the stardust from which we came. Here, I’d like to draw attention to just two of those people.

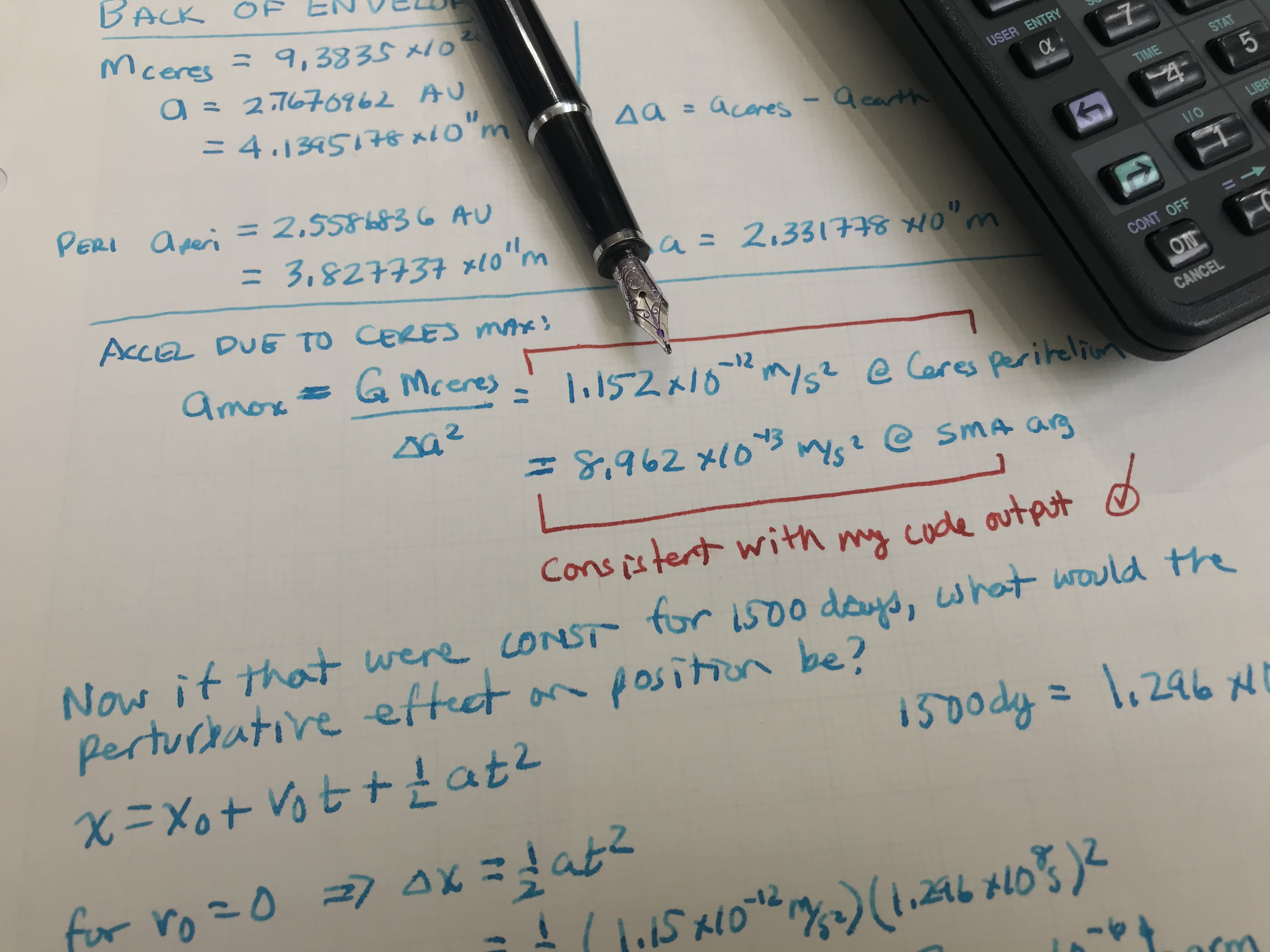

The first person was Ron Hellings. Ron is the Hellings of the “Hellings-Downs” curve, the swooping pattern of correlated signals from the scattered beacons in the pulsar timing array. He and his collaborator, George Downs, first wrote down what that pattern would look like and what pulsar astronomers should look for in a paper in 1983; it was only this week in 2023, forty years later, that their idea came to fruition.

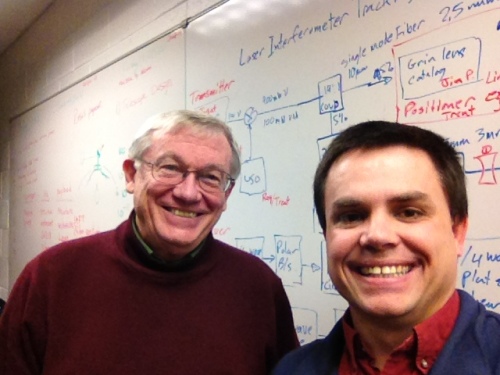

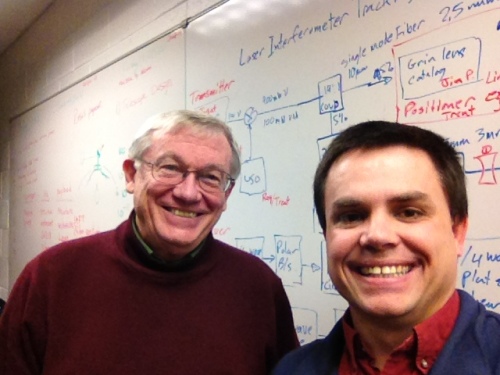

Me and Ron Hellings in 2012, working on the details of a gravitational-wave observatory. [Image: S. Larson]

Sadly Ron passed away on 1 January 2022. At his memorial, when we talked about the important things Ron had discovered about the Universe, the Hellings-Downs curve was one of them.

I have the good fortune of being one of Ron’s academic descendants. I first met him when I was working on my PhD thesis, where we were thinking about the LISA gravitational-wave observatory. It was the beginning of a collaborative enterprise and a friendship that spanned a quarter of a century. We worked on many things together, including LISA, how to think about gravitational-wave signals, how to teach students, and a zillion other things in physics and astronomy. After I finished my PhD I spent two years as his postdoc, when he was at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It was an exhilarating and exciting time, and firmly set me on the path of my career today.

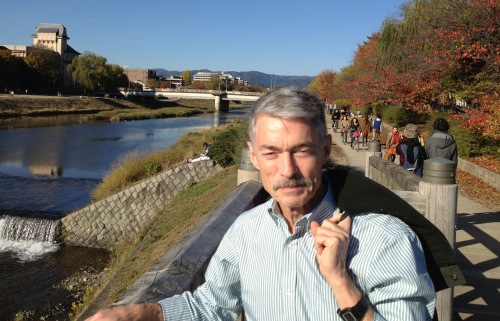

The second person was Steve Detweiler. By the time I was in graduate school, in the late 1990s, Steve was already famous in our community. Like most of those famous people, he was larger than life to us students, but he was always friendly. At meetings, he talked with us at coffee breaks, came to our talks, and sometimes went to dinner with us. I knew Steve for many years after we first met, and we would talk at conferences and meetings where our work on gravitational-waves overlapped.

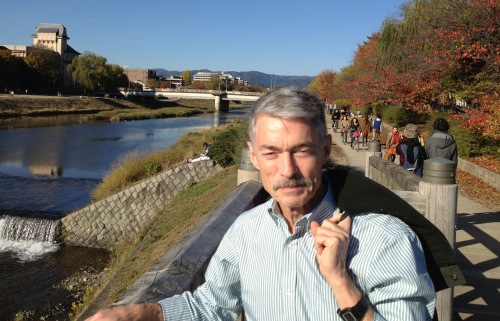

Steve Detweiler. [Image: Eric Poisson]

Steve was well known for many things in his career, but in the late 1970s he was the first person to propose that

pulsar timing could be used to search for gravitational-wave backgrounds; in no uncertain terms, his original analysis sent us down pathway to the discovery that was announced this week.

Steve sadly passed away on 8 February 2016, just three days before the first announcement of the discovery of gravitational waves, and seven years before this week’s announcement of the confirmation of his idea for how to sense the Cosmos anew.

For me, Steve was more than a scientific acquaintance. There came a time when I had to prepare my dossier for tenure as a University professor. The process involves a robust independent evaluation of a person’s contribution to the scientific enterprise. For part of it, the University asks several experts from around the world to make a blunt assessment about the tenure dossier. I got to pick two people, and the University picked four; needless to say it is a terrifying prospect, especially for those of us who don’t have the global stature many of our colleagues have in the field. But I asked Steve to write one of my assessments, and he agreed. I have no idea what he said (his letter was confidential), but whatever it was, the University tenured me, and I owe Steve a great thanks.

My stories and relationships with these senior scientists in the field are not unique — all of us have been encouraged, mentored, and brought into the great adventure of science by colleagues like Ron and Steve. At the NANOgrav press conference, our colleague Maura McLaughlin pointed out that the NANOgrav collaboration involved hundreds of graduate students, undergraduates, and even high school students. Every one of these contributed their time, their unique enthusiasm and energy, and their skills to making the discovery happen.

Not everyone, but some of the members of the NANOgrav collaboration at a recent meeting. People make science happen. [Image: NANOgrav]

The scientific work kept them in the game, growing their skills and propelling them on to whatever is next in their personal journeys. Some of them will go on and become pulsar-timing gravitational-wave astronomers, to be sure. Some will not, but will still become astronomers or physics professors and mentor students of their own. But not all of them — a good many of them will become teachers, or doctors, or engineers, or business leaders, or accountants, or any of a thousand other careers that make the world go round. And in them all, some of what they learned as part of the pulsar-timing-array community will go along with them.

In the end, it’s all about people, and that is the true legacy — the true magic — of the wondrous discovery of the nanohertz gravitational-wave background.

My heartfelt congratulations, respect, and admiration goes out to all my friends and colleagues who made this discovery possible. Excelsior!