by Shane L. Larson

My parents are both natural scientists — my mother is a forester, and my father is a plant ecologist. As kids, we would spend long weeks in the summer camping doing “field research” in the wild backwoods of the Rockies. Tents were optional, and at night I would often lie in my sleeping bag staring up into the blackest night you can imagine.

![The Milky Way, rising over a campsite near Crater Lake, Oregon. [Image by Shane Black, Website]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/shaneblack_milkywaycamping.jpg?w=500&h=333)

The Milky Way, rising over a campsite near Crater Lake, Oregon. [Image by Shane Black, Website]

And for all we know, it does go on forever! The vastness of the Cosmos, especially compared to the typical scales of our everyday lives, is mind-bogglingly large. It is a fact that we have always been cognizant of — our stories, our legends, even our everyday experiences place the sky very far away, beyond the simple reach of human hands. The glitter of distant stars provide an ideal tapestry upon which we can paint our wonderings about the Universe and our place within it. Where did the stars come from? Where did the Earth come from? Where did we come from? These are the oldest questions we know of, uttered around campfires and over late night dinners and in scholarly classrooms for countless generations. The answers to these questions are part of an exquisitely interlinked puzzle that starts with the birth of the Universe, and leads ultimately to me and you. The study of that puzzle is called cosmology.

Cosmology is a branch of science that is a bit like history — we are reconstructing the past history of the Cosmos as a way to understand what we see around us today, and to predict what the ultimate future and fate of Everything might be. We reconstruct that past history by looking deep into the Cosmos, and with the Laws of Nature in hand, attempt to explain what we see. As we have talked about before, looking out into the Cosmos is a kind of Wayback Machine — looking across space is looking back in time. Today, we can see farther across the Universe than at any other time in human history; we have discovered and know more than all the 40,000 generations of humans who have come before us. And we’ve discovered something remarkable; we’ve discovered that in the beginning, something happened. Cosmologists call that something, “The Big Bang,” the origin of Everything that Is.

When studying cosmology, you will often read a sentence about the Big Bang and the Origin of the Universe. The Origin Statement goes something like this: everything in the Universe began in an infinitely dense point smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. What does that mean? The answer is the basis for our current understanding of all of the Cosmos. Let’s parse that question into several smaller questions.

When studying cosmology, you will often read a sentence about the Big Bang and the Origin of the Universe. The Origin Statement goes something like this: everything in the Universe began in an infinitely dense point smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. What does that mean? The answer is the basis for our current understanding of all of the Cosmos. Let’s parse that question into several smaller questions.

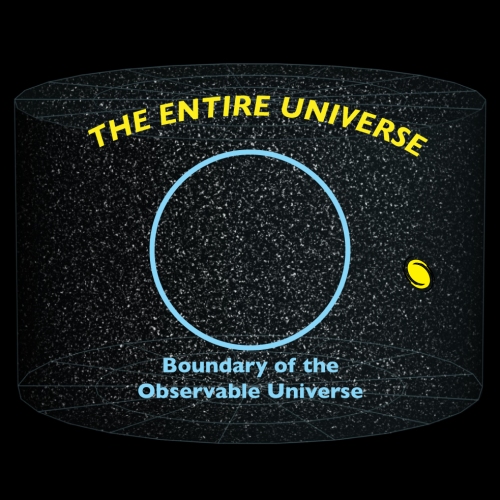

The first obvious question is what do we mean by Universe? Here, we will take the fundamental definition of Universe to be “everything that exists.” But there is an unspoken subtlety in the Origin Statement as we wrote it here — in this case, the use of the word “Universe” actually means “Observable Universe.” What’s the difference between “The Universe” and “The Observable Universe?”

Consider an example from your everyday life — lunchtime. Imagine one sunny day you decide to forego the sack lunch you brought with you and instead decide to go out to lunch with some of your friends. You only have 1.5 hours before you have to be back, and you are walking on foot. You can only walk so fast, so where are you going to go? Perhaps Guy Fieri has pointed you toward an excellent BBQ joint on a late night episode of “Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives,” but that would require either a plane flight or a very long road trip, both of which will take far longer than the 1.5 hours you have. Instead, you confine your attention to restaurants within a certain distance — reachable if you walk as fast as you can for a limited amount of time.

The Universe is kind of the same way — there is a maximum speed that anything can attain, namely the speed of light. Thus, in the age of the Universe, there is a maximum distance over which any information can come to the shores of Earth — the distance that light can travel in the age of the Universe! The “Observable Universe” is that part of the Universe from which we could have received some light that started travelling at the moment the Universe was born, and is just now reaching Earth today (analogous to how far you can walk during your lunch hour). It is a small part of the “Entire Universe,” most of which we know nothing about because the light from there has not had the chance to reach us (analogous to the entire vast world full of restaurants, which you cannot reach during your lunch hour!).

The Observable Universe is just a small part of the Entire Universe. It is bounded by the farthest distance light could have travelled in the age of the Cosmos. If Earth is at the center of this boundary, then light from outside the blue boundary (such as from the yellow galaxy on the right) hasn’t had time to reach us yet. [Illustration by S. Larson]

Now if that doesn’t immediately make sense, don’t worry! It is a disconcerting and unfamiliar idea. The contemplation of big ideas is always a bit uncomfortable, because we’re stretching our brains in ways that it is not used to; that’s the way science works. One way to help settle your mind around unfamiliar concepts and to build intuition is to appeal to analogies. Analogies and metaphors are not perfect, but they help connect the ideas that need to be connected. One of the classic analogies to understand the Big Bang is to imagine other things that stretch and expand.

Consider a large piece of spandex, with a checkerboard on it, as in the figure shown here. The checkerboard pattern is not necessary, but it provides a quick and easy way for us to see and talk about distances. This checkered fabric is an analogy, a metaphor that we use to think about the Universe, and in this picture imagine it stretches far beyond the boundaries of the page of your computer screen. For the moment, I have made the checkers large enough to see, but you could easily imagine them being smaller than what is drawn here, even much smaller (perhaps as small as the proverbial period at the end of the Origin Statement).

Imagine I have two ants sitting on the spandex, one named Xeno (the black ant) and one named Scarlett (the red ant). They have both staked out a square they like, and are staying put, watching closely that the other ant does not move off their chosen territory. This is the case shown in the first figure.

![(L) Consider two ants, Xeno and Scarlett, on a stretchy sheet representeding the spacetime fabric of the Cosmos. (R) When the Cosmos expands in every direction and at every point, the two ants get farther apart. [Illustration by S. Larson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/spacetimestretch01.jpg?w=500&h=320)

(L) Consider two ants, Xeno and Scarlett, on a stretchy sheet representeding the spacetime fabric of the Cosmos. (R) When the Cosmos expands in every direction and at every point, the two ants get farther apart. [Illustration by S. Larson]

What is interesting is that every square in the fabric of our Universe is expanding — the squares are getting larger, and everything is getting farther apart. No matter how tiny every square started, if we wait long enough, it gets bigger. The consequence is that from the perspective of anyone anywhere in the Universe, every other point is flying away from them. Consider a few more ants: Xeno, Scarlett, Kermit (the green ant) and Indigo (the blue ant). If each one of them measures the distance to every other ant, they find that if they wait a while, the distance to every other ant increases. From the perspective of any ant, firmly rooted to their little territory in the Cosmos, every other point in the Universe is slowly getting farther and farther away, no matter what direction they look.

Imagine an army of ants (clockwise from the top: Kermit, Scarlett, Indigo, and Xeno). If they all watch each other as the Universe expands, they think ALL other ants are moving away from them, no matter what direction they are. [Illustration by S. Larson]

On the surface, this story sounds fantastical, almost beyond belief. We can always make up fantastical ideas about the nature of the Cosmos, but for those ideas to move beyond mere speculation and into the realm of science, we must be able to test those ideas. There must be something we can look for, something that we can observe. In the case of cosmology, there is.

One of the things that physicists know about the world is that if you compress things they get hot. This is the principle behind pressure cookers, this is why it is hot in the core of the Earth, and this is why the Sun burns hydrogen in its core. When the pressure goes up, things get hot! If the Universe is expanding today, we can imagine running the movie backward in time, watching everything run backward toward the Big Bang. Because we see everything flying apart now, when we run the movie backward what we see is the entire Observable Universe being compressed down into a small point. The pressure in that point would have been enormous, which means it would have been tremendously hot. If that were true, there should be some thermal signature of that early, hot, dense state of the Cosmos.

One of the things that physicists know about the world is that if you compress things they get hot. This is the principle behind pressure cookers, this is why it is hot in the core of the Earth, and this is why the Sun burns hydrogen in its core. When the pressure goes up, things get hot! If the Universe is expanding today, we can imagine running the movie backward in time, watching everything run backward toward the Big Bang. Because we see everything flying apart now, when we run the movie backward what we see is the entire Observable Universe being compressed down into a small point. The pressure in that point would have been enormous, which means it would have been tremendously hot. If that were true, there should be some thermal signature of that early, hot, dense state of the Cosmos.

There is such a signature. Arriving on Earth from every direction on the sky, is a faint fog of microwave radiation, known as the Cosmic Microwave Background. It is the light that was released from the birth of all the atoms in the Cosmos, 400,000 years after the Big Bang. Before this time, the Universe was so hot and dense that atoms could not hold together; they would constantly crash together and break apart into the fluff from which they are made, melting back into the primordial soup of light and sub-atomic particles. But as the Universe expands, it cools slowly until atoms could hold together. The moment that happened, the soup immediately thinned and the light flew free, carrying the message of the birth of the atoms.

This picture of the Cosmic Microwave Background is the most accurate map every made of the microwave sky; it is the youngest picture of the Cosmos we have ever taken, and the strongest piece of evidence we have that the Big Bang unfolded in the way we have just discussed. This picture, an image of the Cosmos very shortly after its birth, is one of the greatest legacies of our race. It captures, in an exquisite map of subtle patterns and colors, the ability of our species to reduce our ignorance, to become more enlightened about the Cosmos and our place in it.————————————

This post is part of an ongoing series, celebrating the forthcoming science series, Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey by revisiting the themes of Carl Sagan’s classic series, Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. The introductory post of the series, with links to all other posts may be found here: http://wp.me/p19G0g-dE