by Shane L. Larson

There are many exotic phenomena in astrophysics — some pervade the public consciousness, and others do not. Most folks have heard of the “Big Bang” and probably about “dark matter.” Fewer people have heard of the “Cosmic Microwave Background” or “neutron stars.” Perhaps even fewer have heard of “cosmic strings” or “radio jets.” But of all the strange and wonderful things astronomers and physicists have contemplated, the most universally known and recognized are probably “black holes.” Just about everyone has heard of black holes, and just about everyone has some cool science factoid they know about black holes and keep in their pocket — they pull the factoid out anytime the subject of black holes come up because the factoids typically MELT YOUR BRAIN.

On the left, an optical image from the Digitized Sky Survey shows Cygnus X-1, outlined in a red box. Cygnus X-1 is located near large active regions of star formation in the Milky Way, as seen in this image that spans some 700 light years across. An artist’s illustration on the right depicts what astronomers think is happening within the Cygnus X-1 system. Cygnus X-1 is a so-called stellar-mass black hole, a class of black holes that comes from the collapse of a massive star. New studies with data from Chandra and several other telescopes have determined the black hole’s spin, mass, and distance with unprecedented accuracy.

I find black hole factoids to be a curious mix of some things that are true, some things that are speculative but possibly true, and some things are are outright fiction. Where do all of the exotic facts about black holes come from, how do we all learn them, and why are some right and some wrong? Wondering about this led me to contemplate when I first heard about black holes.

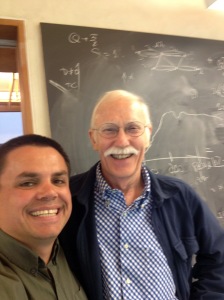

Black holes have long been a passion of mine — my mom will tell you I was always kind of obsessed with them. But when did I first hear about and learn about them? I certainly can’t answer that question definitively, but I do know some things about my early exposure, so I can try to understand what strange and awesome ideas first attracted my attention.

The earliest encounter of which I am certain is during the 1979/1980 timeframe. This was the time that many people saw Disney’s epic space opera The Black Hole, replete with adorable robots, killer robots, really awful bad dialog, and archetypical mad scientists. It has often been derided for its scientific inaccuracies (most notably by Neil deGrasse Tyson [link]). I definitely saw The Black Hole. Multiple times. And I still watch it sometimes. Neil’s right, there is a lot of inaccurate science about black holes in The Black Hole, but there is a lot that I think was okay too (more on that later). There are definitely modern movies that get the science more uniformly correct (Interstellar), but I don’t mind The Black Hole — certainly not as much as Neil. The point here is this is a known anchor point in my love affair with black holes.

The earliest encounter of which I am certain is during the 1979/1980 timeframe. This was the time that many people saw Disney’s epic space opera The Black Hole, replete with adorable robots, killer robots, really awful bad dialog, and archetypical mad scientists. It has often been derided for its scientific inaccuracies (most notably by Neil deGrasse Tyson [link]). I definitely saw The Black Hole. Multiple times. And I still watch it sometimes. Neil’s right, there is a lot of inaccurate science about black holes in The Black Hole, but there is a lot that I think was okay too (more on that later). There are definitely modern movies that get the science more uniformly correct (Interstellar), but I don’t mind The Black Hole — certainly not as much as Neil. The point here is this is a known anchor point in my love affair with black holes.

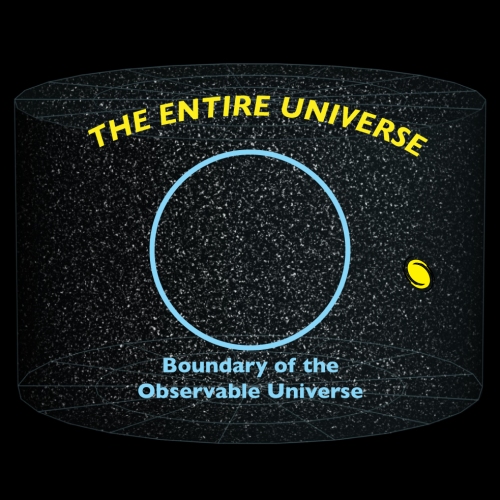

So what could a movie like The Black Hole teach me about real black holes? If you ask almost anyone, they know the correct fundamental thing: a black hole is an object whose gravity is so strong, not even light can escape — even The Black Hole got that right. Since nothing can travel faster than light, nothing can escape. If you fall into a black hole, your fate is sealed. It is this idea of being trapped forever, without recourse or hope of rescue, that lies at the heart of our fascination with black holes. They are strange; indubitably. But to be inescapable suggests a kind of absolute and infinite supremacy.

Me in elementary school. I’m not sure what I’m doing, but I’m pretty sure I’m not getting into trouble! [Image: Pat Larson]

It is a book filled with great pictures from an exquisite generation of space probes, and from the best telescopes the world knew in the pre-Hubble era. But the art and scientific illustrations are what sucked me in. Paintings of the surface of Venus. Speculations of what weird alien lifeforms evolution could have created. Stupendous cutaways of planetary interiors and atmospheres. All of it was linked together with Gallant’s trademark lucid storytelling. This ode to the Universe captured my mind and imagination and never let go. That first copy my parents gave me was read cover-to-cover, and carried for miles and years everywhere I went, pulled out of my backpack in moments of wonder and curious indulgence.

Near the end of the book, Gallant talks about black holes in just 4 short paragraphs, but accompanies the text with a lavish, full-page artist’s idealization of a black hole in space, tugging on a nearby star, bending the shape of spacetime, and absorbing a beam of light that was inexorably caught in its pull.

He asks in the caption of the picture, “Can you imagine a star so massive that its gravitation eventually crushes it out of existence, leaving only a black hole in the sky?” This is classic Gallant, imploring the reader to immerse themselves in the mystery, throw caution to the wind, and employ their imagination — take what little knowledge you have and simply speculate. That is where good ideas come from, and it is the basis for all science.

In many ways, the reason you and I are having this little blog conversation is precisely because astronomers know that black holes exist in Nature and are the central players in many astrophysical phenomena. But reading Gallant’s text it is clear that when he wrote Our Universe, the existence of black holes was still a subject of much debate among scientists. Today there are many ways that we have measured the properties of black holes and confirmed their existence, not the least of which are the many that have been detected via gravitational waves. But still, pictures of black holes remain elusive. The best we have so far is the Event Horizon Telescope picture, a silhouette of a black hole against the backdrop of stuff around it.The picture in Gallant’s book is an attempt to show a black hole as a three dimensional object in real space, but how do you do that? It was a noble attempt, and it is certainly not what a black hole looks like, but it served its purpose — it got my attention, it fueled my imagination, and it made me ask questions then go see if the answers were known. To this day I keep copies of Our Universe nearby — one in my office and one in my study at home. It is never far from my mind nor my fingertips, and I often pull it down and lose myself in the epic stories it tells.

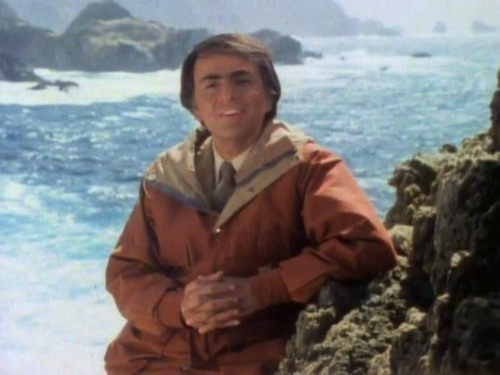

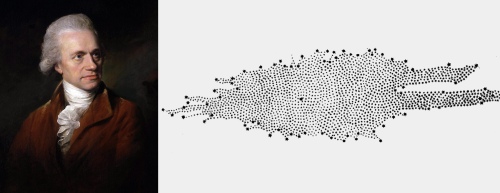

The other thing I know happened to me in the fall of 1980 was my first exposure to Carl Sagan’s Cosmos. Starting in late September, every Sunday night, I sat rapt on my parents’ living room floor in front of the television, whisked away to worlds and places in the Cosmos I had only previously imagined, transported by the magic of film, the lilting and elegant soundtrack of classical music, and Sagan’s poetic and sonorous narrative. One of the most widely known episodes is Episode 9, “The Lives of the Stars” which famously begins with Sagan declaring, “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the Universe.”

Sagan uses his famous declaration about pies to introduce the concept of the chemical elements — the atoms from which all the beautiful and complex structures of Nature are built. Beyond the simplest elements — hydrogen and helium — very little was created when the Cosmos was born. Almost everything on the periodic table is created by stars during their lifetime, and a great deal of it (the heaviest elements) during the catastrophic death throes we call supernovae and gamma ray bursts. In telling us about the death of stars, Sagan uttered the magic words I had heard before — black hole. In his trademark penchant for poetic description, he called it “a star in which light itself has been imprisoned.”

Sagan’s Cosmos was the first place I was introduced to the ideas of black holes in the context of general relativity, beginning with masses curving space and affecting the motion of other masses, and also a discussion of the principles of black holes as tunnels [Images from Ep 9: “The Lives of the Stars”]

For many of us, our interest in black holes might be piqued by these kinds of exposures, and then we go back to our lives as dental hygienists or soybean farmers or city managers. But this was all still swirling in my mind when I entered college, and in the true traditions of higher education, my exposures took those latent passions and exploded them into what would become my life. I was an undergrad at Oregon State University and at that time there was a stupendous class on campus called “Rocks & Stars,” run by the indomitable Julius Dasch. This was one of the most popular classes on campus, and had a regular stream of guest speakers who visited and talked to us about cool stuff. I have strong memories of one visit from J. Craig Wheeler, a supernova expert from the University of Texas at Austin.

Supernovae are one of the pathways for making black holes in the Universe, and Wheeler gave us a spectacular talk that culminated with him reading to us from a science fiction book he wrote, called “The Krone Experiment.” I won’t give it away (go read it!) but what I remember from the talk was Wheeler talking us through what would happen if you were standing on a sidewalk and a micro-black hole came booming up out of the ground next to you. What would you see and experience? It’s the sort of question that just captures your brain and won’t let go. To be honest, it was the perfect question to ask a young scientist in the throes of deciding to commit their career to studying these enigmatic objects.

Supernovae are one of the pathways for making black holes in the Universe, and Wheeler gave us a spectacular talk that culminated with him reading to us from a science fiction book he wrote, called “The Krone Experiment.” I won’t give it away (go read it!) but what I remember from the talk was Wheeler talking us through what would happen if you were standing on a sidewalk and a micro-black hole came booming up out of the ground next to you. What would you see and experience? It’s the sort of question that just captures your brain and won’t let go. To be honest, it was the perfect question to ask a young scientist in the throes of deciding to commit their career to studying these enigmatic objects.

I think every one of these stories illustrates a key fact in my mind: it didn’t matter what I heard about black holes in my youth, only that I did hear about black holes. Exposure did what it should: it filled my head with all kinds of possibilities, all of them totally brain-melting, and made me pay attention and ask questions later.

This last point is the most important point here: we want people to ask questions. Either because they are confused, or because they are idly curious, or because they want to learn more. To that end, having mind bending movies like The Black Hole is stupendously important, and I don’t care if they get the science perfectly right! I have colleagues who often grouse about bad science in movies, complaining vociferously that the producers should have taken a basic science class, or gotten a good science advisor. They proclaim, “Is it really that hard to get the science right? The right science is just as cool!”

This last point is the most important point here: we want people to ask questions. Either because they are confused, or because they are idly curious, or because they want to learn more. To that end, having mind bending movies like The Black Hole is stupendously important, and I don’t care if they get the science perfectly right! I have colleagues who often grouse about bad science in movies, complaining vociferously that the producers should have taken a basic science class, or gotten a good science advisor. They proclaim, “Is it really that hard to get the science right? The right science is just as cool!”

But people aren’t watching The Black Hole to learn science (I certainly wasn’t) — they are being entertained, itching a part of their brain that wants to be asked “is that even possible or real?” And that serves its purpose, because eventually every one of them ends up in an audience somewhere at a public lecture and raises their hand and asks someone like me “is what happened in the movie real?” THAT is where we get the science right. The movie’s job was to put a question in someone’s mind, to make them care enough to know what the right answer might be, and then in some other part of their lives have some discussions about science, what is known, what is not known, and what the other mysteries of the Cosmos might be.

————————–

This post is the last in a series about black holes.

Black Holes 01: Imaging the Shadow of Darkness

Black Holes 02: What are black holes made of?

Black Holes 03: Making black holes from ordinary stuff

Black Holes 04: Singularities, Tunnels, and Other Spacetime Weirdness

Black Holes 05: Inklings & Obsessions (this post)

![There is nothing quite like standing out in the dark and seeing the Cosmos with your own eyes. [Grand Tetons, by Royce Bair; http://NightScapePhotos.com/ ]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/roycebair_grandtetons2.png?w=500&h=328)

![The Blue Marble, 2012. [NASA]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/bluemarble_north_america_from_low_orbiting_satellite_suomi_npp.jpg?w=500&h=500)

![One of the most often reproduced Apollo images; Jim Irwin on the plain at Hadley, in front of the Lunar Module Falcon and Lunar Rover. [NASA Image AS15-88-11866]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/as15-88-11866hr.jpg?w=500&h=504)

![A white dwarf is the skeleton of a star like the Sun, long after it has died. It has about the mass of the Sun, but is the size of the Earth. [Image by STScI]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/stsciwhitedwarf.jpg?w=500&h=257)

![A few of the radio telescopes that make up the Very Large Array (VLA) near Socorro, New Mexico. The VLA is one of the premiere radio astronomy observatories on planet Earth. [Image by S. Larson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/vladishes.jpg?w=500&h=180)

![There are all kinds of ways to imagine talking to aliens. [Calvin & Hobbes, by Bill Watterson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/calvinufoslandhere.jpg?w=500&h=164)

![Drake's original pictorial message, to test communication without preamble. [Image from D. Vakoch, in Mercury (March, 1999)]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/drakefirstmessage.jpg?w=204&h=300)

![A pulsing radio signal, showing how a message consisting of 1's (signal on) and 0's (signal off) can be encoded without writing the characters "1" or "0." [Image by S. Larson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/radiosignal.jpg?w=500&h=191)

![(L) The Arecibo Message string, arranged in 73 rows and 23 columns. Even in text, your eye can see patterns emerging. (C) The same message shown as a shaded grid, making the patterns more clear. (R) The same image colorized for discussion. [Images by S. Larson; R image from Wikimedia Commons]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/arecibovertical.jpg?w=500&h=652)

![(L) The Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde, one example of an abandoned Anasazi city [National Park Service image] (R) The Kalasasaya and lower temples at Tiwanaku. At equinoxes, the sun shines into the Ponce Monolith, aligned in the main door. [Image from Wikimedia Commons]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/lostcivilzations.jpg?w=500&h=166)

![The Milky Way, rising over a campsite near Crater Lake, Oregon. [Image by Shane Black, Website]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/shaneblack_milkywaycamping.jpg?w=500&h=333)

![(L) Consider two ants, Xeno and Scarlett, on a stretchy sheet representeding the spacetime fabric of the Cosmos. (R) When the Cosmos expands in every direction and at every point, the two ants get farther apart. [Illustration by S. Larson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/spacetimestretch01.jpg?w=500&h=320)

![Antares is in its red giant phase, and is larger than the orbit of Mars! [Image from Wikimedia Commons]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/antaresredgiant.png?w=500&h=500)

![My childhood ambitions, left to right: (1) astronaut [this is Heidemarie Steefanyshyn-Piper on STS115], (2) Captain Kirk, (3) Carl Sagan, (4) Indiana Jones](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/heroes.jpg?w=500&h=138)

![(L) NGC 3448 as seen by GALEX and Spitzer [Image, JPL/NASA], (R) Supernova SN2014g.](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/ngc3448_sn2014g.jpg?w=500&h=251)

![Nuclear powered starship concepts that, in principle, are not outside the boundaries of our technology. (L) Starship Orion; (C) Project Daedalus; (R) Bussard Ramjet. [Images from Cosmos: A Personal Voyage] For many detailed starship concepts, see the book The Starflight Handbook by Eugene Mallove.](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/starshipscosmos.jpg?w=500&h=250)

![The black hole at the center of the Milky Way, surrounded by a swarm of stars and the strained tendrils of gas clouds and stars that have been eaten by the black hole. [Image from European Southern Observatory]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/g2cloud_eso1151a.jpeg?w=500&h=281)

![The Milky Way rising over Mt. Hood and Lost Lake, Oregon. [Imaged by Ben Canales, http://www.thestartrail.com ]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/lostlakemounthood_bencanales.jpg?w=202&h=300)

![(L) Lord Rosse's first sketch of M51 in 1835, showing the spiral structure seen through the Leviathan. (R) A modern HST image of M51 [NASA/ESA].](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/messier51rossehst.jpg?w=500&h=178)

![Henrietta Swan Leavitt at her desk [Harvard College Observatory].](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/henriettaleavitt02.jpg?w=300&h=204)

![Hubble at the eyepiece of the 100" Hooker Telescope on Mount Wilson [Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images].](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/hubblehooker.jpg?w=252&h=300)

![Our current best understanding of the structure of the Milky Way, as seen from above the galaxy. [Image by European Southern Observatory].](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/1024px-artists_impression_of_the_milky_way_updated_-_annotated.jpg?w=500&h=500)