by Shane L. Larson

The inimitable Mary Fahl has a remarkable song that I listen to all the time, especially on days when it seems impossible that the world has not totally fallen apart. It is a sonorous and passionate piece called “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright.” It opens:

Blind Willie Johnson in a capsule singing ‘bout the soul of man Encoded traces of the human race and what we understand A human choir out in the distance trav’ling by a satellite Symphonic strains of our existence burned into a single byte

For the uninitiated, Mary’s song may seem strange or obtuse — lyrical renderings of language that may have philosophical meaning if contemplated long enough, or may inspire deep visceral emotions if interpreted in certain ways, or simply seem to be pleasant nonsense in the way only songs and poetry can be.

But in reality, Mary’s song is a tribute, heartfelt and full of wonder, for one of our species’ most audacious and hopeful acts: the creation of a message that will far outlive our civilization, promising whoever hears it that we are sometimes better than we often are. The message was created, physically engraved in precious metals, and cast out into the wild voids of the Cosmos, never to be seen again.

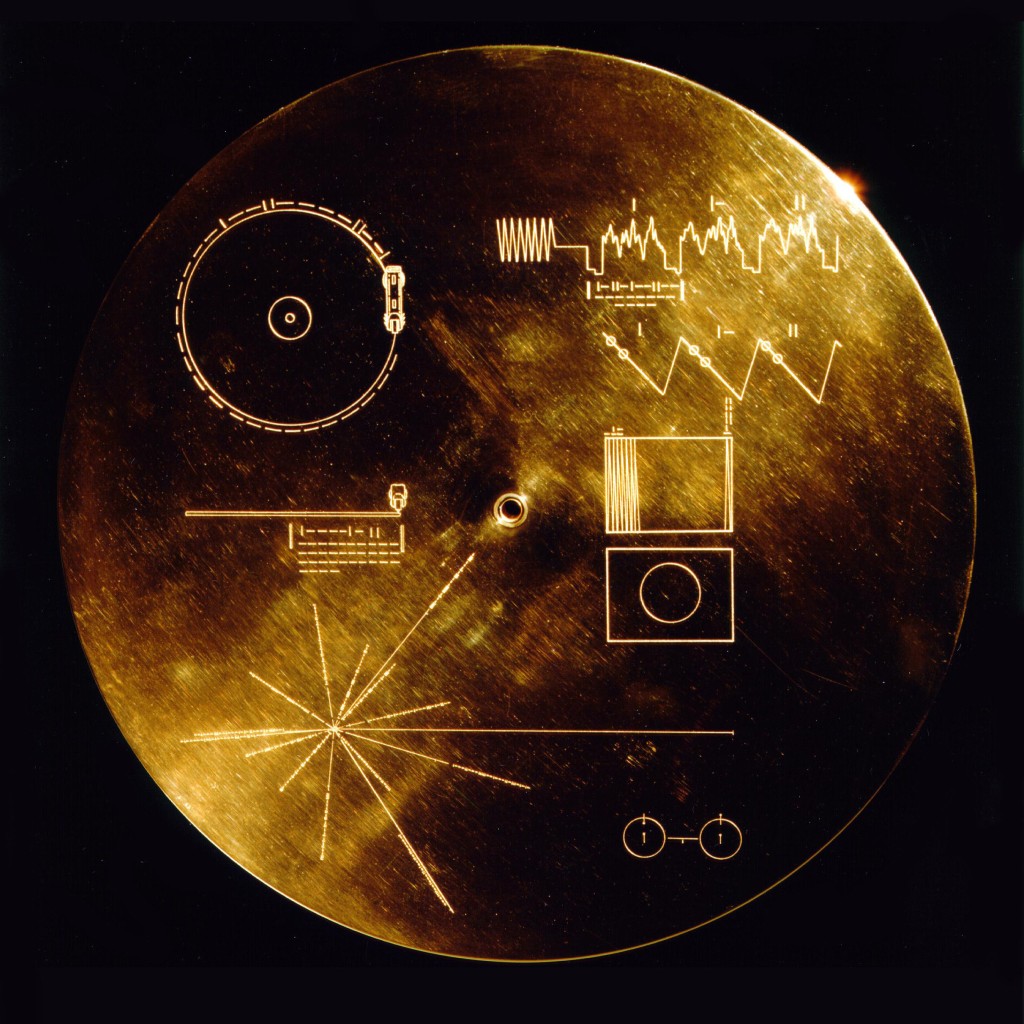

That message is known as the Voyager Golden Record. Two copies of the record were minted from disks of copper plated in gold, shrouded beneath protective covers of aluminum, and mounted on the side of each of the two Voyager spacecraft.

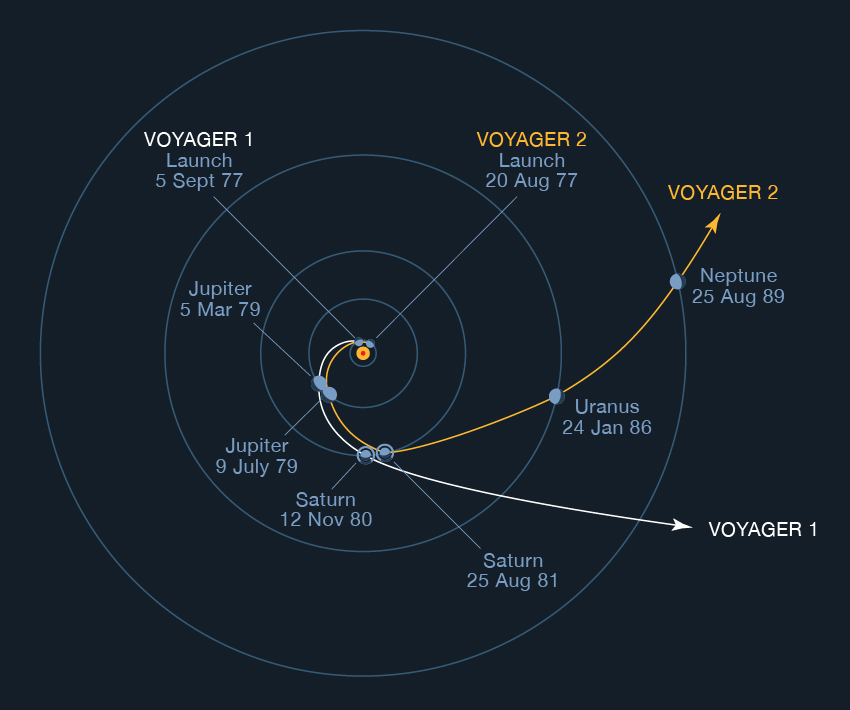

Launched 16 days apart in the autumn of 1977, the Voyager spacecraft were ostensibly part of humanity’s first reconnaissance of the solar system, sent to explore the giant worlds of the outer solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. They swung by each world, dutifully snapping pictures and radioing their precious scientific data back to the distant rock from which they hailed. As they passed by each world, gravity latched on to them, propelling them ever faster and farther, on to their next destination.

Voyager 1 passed Saturn in November of 1980, and the Ringed Planet flung it up and out of the plane of the solar system, toward the constellation of Ophiuchus. In August of 1989, after a twelve year journey, Voyager 2 passed by Neptune, letting the icy giant’s gravity swing it down and out of the solar system, propelling it in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius. After fleeting and tantalizing glimpses of our cosmic neighborhood, the Voyagers have started the long, slow sail to the stars. Today they are the most distant physical artifacts of the human race, both of them more than 20 billion kilometers away, the Sun and Earth mere flecks of distant light.

Powered by small nuclear generators, the Voyagers’ energy is nearly spent. They will dutifully continue to transmit faint bleeps of information back to Earth, but within a decade or so they will fall silent and grow cold, hurtling ever onward toward the stars. Time, space dust, and cosmic radiation will take their toll on these artifacts of Earth, but the Golden Records were designed to stall such inevitable decay for as long as possible. Made of metals that are unreactive and change slowly over time, and encased behind protective aluminum covers, they should resist the long slow death, surviving for a billion years or more..

But what possibly could we have put on the Golden Records to warrant such care and concern about their survival? Mary Fahl told us up front:

Encoded traces of the human race and what we understand

Within the limitations of a physical object that could survive a billion year journey into deep space, we captured what we could about our species, the planet on which we live, the lifeforms we share the Earth with, and the meager understanding of the Cosmos we have gained. Together with greetings in many languages of the planet, and a selection of music from around the world, we engraved the information on 12-inch disks of gold covered copper, and sent them to the stars. It was a gesture of hope and optimism that, in some imagined future, an intelligent species somewhere across the empty sea of space might stumble across Voyager and be able to know something about who we were, faint echoes of a lonely planet and species that once dreamed of sailing to the stars.

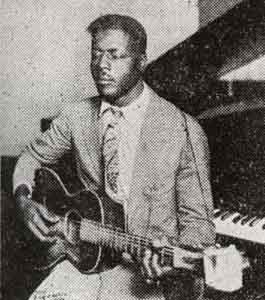

The key elements of the Voyager record are the protective cover, an included stylus (phonograph needle) to play the record, 115 images, a collection of the “sounds of Earth,” spoken greetings in 55 languages, and 90 minutes of music in 27 tracks. Blind Willie Johnson is the second to last track, singing Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground, a blues Gospel song, with no words but Johnson murmuring and humming along with his soulful guitar picking.

By today’s standards, the amount of data on the record is miniscule — a handful of images that are 512 x 384 resolution, and only 90 minutes of music. But that’s all there is, a small snapshot of life on Earth at the end of the 20th Century. It is likely one of the only artifacts of humanity that will survive our species; for some distant intelligence that might someday find Voyager, it is the only thing they will ever know of us.

The assumption we are making is that whomever might find Voyager will make an attempt to decode the Record. It’s an all together human assumption — if you found a bottle washed up on the seashore, a message carefully preserved inside, would you open the bottle to read it? Of course you would! In our optimism, we trust the receivers of our message will do the same.

On the surface, it seems to be an audacious thought, that a message encoded on a facsimile of a phonograph record could be received and decoded by an extraterrestrial who knows absolutely nothing about us, our technology, our species, our cultures, or our languages. But the message was designed with precisely that concern in mind. Astronomers call the idea of receiving such a message “communication without preamble,” and believe understanding it is predicated on a single fact: that the receiving civilization is technologically skilled.

One of the great truths of the Universe, and perhaps the greatest mystery, is that everything is governed by an immutable set of rules that we call The Laws of Nature. The idea, the logical chain of reasoning, is that if you are capable of travelling into space to discover Voyager, it means you have a deep understanding of those self-same laws, enough so that you can harness them to travel the void of space yourselves. So we encoded the Voyager message using the common foundations of astronomy, physics, and mathematics that apply in every corner of the Cosmos, and trust that an understanding of those foundations will provide enough of a clue to decode Voyager’s precious cargo of sounds, music, and images.

If you think deeply about this, you might argue that an alien species that recovers Voyager may not have eyes to see as we do, so images may not carry the same meaning. They may not have ears to hear as we do, so music may not be perceivable in the same way. But consider: there are many phenomena in Nature that our senses cannot perceive, yet our intellect and technology make us perfectly capable of detecting and understanding. If an extraterrestrial species is technologically capable, we think they will similarly be able to apply their intellect to understand the story Voyager has to tell.

How do you decide what to include in a message you are sending to the stars? What do you put in a time-capsule to represent our planet and ourselves to an audience we will never know? What do you send to a world and a biology and a history and an intellect completely alien to our own? What do you want beings a million years from now to know about us?

We could be cynical, we could be optimistic, we could be realistic, we could be practical. What should we be?

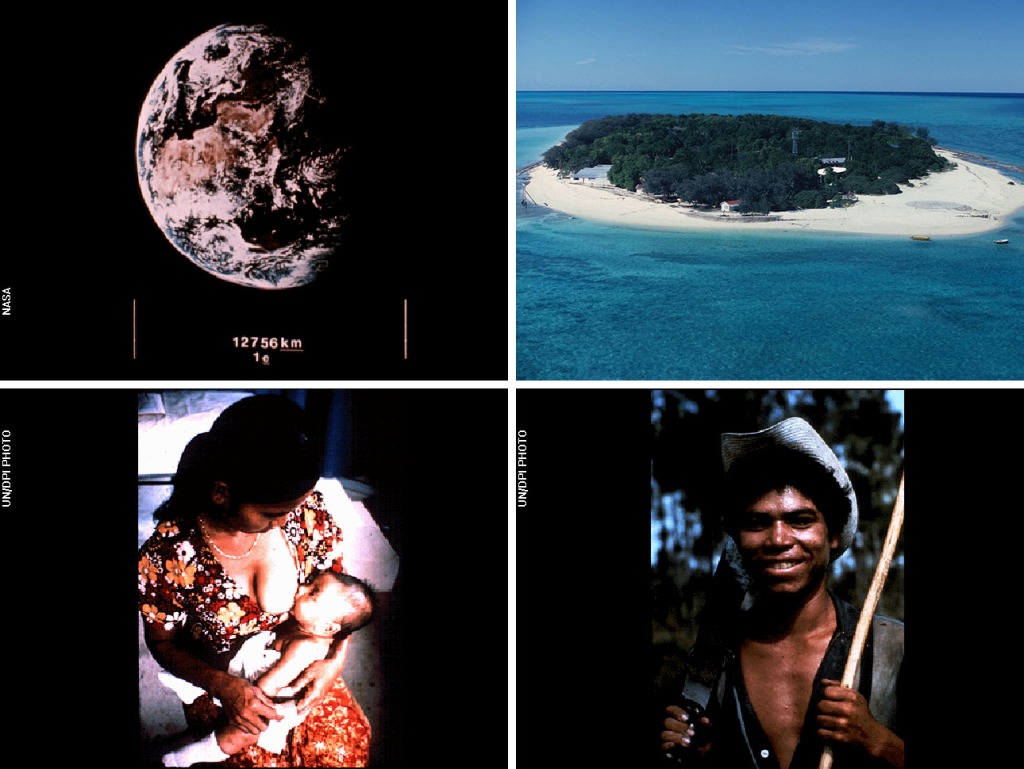

It is often pointed out that we could have included images and messages about our great failings. The wars we fight, the violence we inflict on one another, our great failings in justice and equity for all the citizens and life of the planet. We could have included images of atomic mushroom clouds, of dead school-children, of wasted and decimated landscapes destroyed by our short-sighted obsessions. But we didn’t do that. We took a very neutral stance, perhaps a sanitized vision of our world. We included pictures of our planet from space, of a tropical island, of a mother and child, of a farmer in Guatelmala, and 111 others. A cynical person might suggest we were being overly deceptive, and not showing the truly ruthless and sad character of our species. Perhaps, but I think not.

No, flipping through the image library of the Voyager Golden Record one also gets the sense that this is not just who we are, but what we hope we are — a species that is living through the challenges of our own adolescence, a species that is for the moment surviving, and a species that aspires and believes that many thousands of years hence, our descendants will still be here, wiser and better off than we. We tried to choose a series of images that say we learned enough to build Voyager, and while we’re aware of the dangers we currently face, we are also aware that we are part of a much larger Cosmos. Our meager collection of images and music is a realization of what we have learned, manifested in the optimistic act of constructing an impossibly limited message containing a few precious tidbits of life on Earth, from a species called “humans.”

And we tossed the message into the Cosmic Void, knowing not where the tides of space might take it.

There is absolutely no consequence if Voyager is never found, nor if the message is never decoded. There is a certain solace we gain from the mere notion that it might be found and might be decoded. Perhaps that solace is rooted in a deep fear — the fear that we are alone in the Cosmos, and everything that we are and think and do will someday perish, extinguished utterly from the Universe.

But I much rather like to think that the solace is rooted in optimism. We believe that it is worth shouting into the Void, shouting that we were here and this is who we were. We believe that, perhaps, there will be beings as intelligent and curious and emotional as we, and that they too might find joy in the discovery of Voyager. We imagine they might feel inexorably compelled to decode the carefully constructed message, and discover that they also are not alone in all the expanse of the Cosmos. We imagine that they too might be struggling through their own adolescence, hoping to not destroy themselves. We imagine that if they receive this small, meager message from Earth, the knowledge that they are not alone might help them somehow. We imagine that such a message might help us.

It is remarkable to think that the act of creating the Voyager Record is an act of optimism, and precisely what Mary Fahl’s lyrical exploration suggests to me. It suggests that despite all the challenges our species faces, despite all the clear failures that we foist upon ourselves, that some part of us still knows the remarkable things we can achieve, and we imagine the good that could result.

In days of gloom, in days of sadness, no matter what we do here on Earth, Voyager sails ever onward, its Golden Record cradled carefully on board, a message for a billion years from now. Perhaps, as Mary noted, “everything’s gonna be alright.”