by Shane L. Larson

Humanity is simultaneously blessed and cursed with one of the most ingenious creations of Nature: our imaginations. Our brains have developed not just to run our bodies, and not just to absorb sensory data from the world. They store all the vast myriad of experiences we have and then, at a later time, recall that data for the express purpose of inventing ideas that may or may not have anything to do with reality.

Humanity is simultaneously blessed and cursed with one of the most ingenious creations of Nature: our imaginations. Our brains have developed not just to run our bodies, and not just to absorb sensory data from the world. They store all the vast myriad of experiences we have and then, at a later time, recall that data for the express purpose of inventing ideas that may or may not have anything to do with reality.

An excellent example of how your brain works can be found in a simple game my daughter and I play at restaurants while we’re waiting for our food. We call it “The Napkin Game.” One person draws a simple line doodle, without lifting the pen, then the other person takes that doodle, looks at it from all angles, then adds more lines to turn it into a picture. When you draw a doodle for your partner, you don’t a priori know what it will be turned into. That’s the magic of brains! Any random doodle could be Batman’s cowl, or a Wonka Bar, or a turtle. Your brain takes a little bit of visual input, maps it onto one of the trillions of neural connections in your mind, and makes something new!

An example of the Napkin Game. One person draws a simple line doodle, and the other person adds to it to make a picture.

One of the most important things your imagination does, is it extrapolates into the future. Sometimes it makes up extrapolations out of whole cloth that likely have little bearing on reality (though they may be perfectly entertaining, if not desirable, daydreams). I count among such extrapolations imagined futures where zombies have taken over the world, Apple Slice has made a comeback, or I am close personal friends with Queen Elsa of Arendelle. But very often, the extrapolations are really simulations — attempts to divine a realistic future. This is the origin of wonder, of anticipation and excitement, and also of fear (particularly fear of the unknown). Imagination uses both of these extrapolations in the game we call science.

The most remarkable thing about imagination is that it knows no boundaries. T-rex flying a fighter jet? No problem. I’m really Walter Mitty, a member of MI:6 who cleans up after Bond? Duh. Every kind of particle we have ever seen maybe has an undetected and completely made up “super-symmetric” partner particle? Sure, that sounds cool to think about!

![Examples of imagination, possibly run amok. (L) Dinosaurs flying fighter jets [Lego model; dino added by S. Larson]. (C) The Standard model of particle physics. (R) The "SuperSymmetric" addition to particle physics, imagined by some physicists.](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/dinosusy.jpg?w=500&h=144)

Examples of imagination, possibly run amok. (L) Dinosaurs flying fighter jets [Lego model; dino added by S. Larson]. (C) The Standard model of particle physics. (R) The “SuperSymmetric” addition to particle physics, imagined by some physicists.

Consider the question of life in the Cosmos. Is there life elsewhere? Are we a singular instance of life, or is there a vast froth of life-filled worlds filling the deep, deep dark of the Universe?

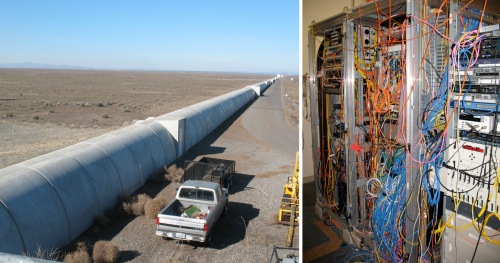

![One dish in the Very Large Array (VLA) near Socorro, NM. [image by S. Larson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/lonelycosmos.jpg?w=500&h=153)

One lonely dish in the Very Large Array (VLA) near Socorro, NM, staring out into the Cosmos. [image by S. Larson]

(1) The Earth is unique. We are a singular instance of the music we call life, a lone voice shouting vainly into the vast, dark cathedral of the stars.

(2) The Cosmos is teeming with life, a vast ecosystem of atoms that have organized into patterns capable of replicating and contemplating their own existence.

Arthur C. Clarke once famously summarized these extremes, saying “Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” The amount we are terrified by this thought is the fault of our imaginations. We are inherently social creatures — we thrive on contact, discussion, and shared common experience. All of us have, at some point in our lives, experienced profound loneliness — being lost, being trapped, being left out by our peers. When we imagine being alone in the Cosmos, our brain magnifies that sense of loneliness a trillion-fold. What gets simulated is not the Earth all alone, but ourselves all alone — what if I were alone in the Cosmos, lost in the vast dark? We anthropomorphize the entire human race, mapping our own personal feelings onto 7 billion other souls.

Arthur C. Clarke once famously summarized these extremes, saying “Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” The amount we are terrified by this thought is the fault of our imaginations. We are inherently social creatures — we thrive on contact, discussion, and shared common experience. All of us have, at some point in our lives, experienced profound loneliness — being lost, being trapped, being left out by our peers. When we imagine being alone in the Cosmos, our brain magnifies that sense of loneliness a trillion-fold. What gets simulated is not the Earth all alone, but ourselves all alone — what if I were alone in the Cosmos, lost in the vast dark? We anthropomorphize the entire human race, mapping our own personal feelings onto 7 billion other souls.

In the opposite case, our imagination proposes a Cosmos completely contrary to the normal hubris that humanity wields. Despite our proclaimed belief in the fundamental tenets of Copernican astronomy, where the Earth is not the Center of All That Is, we certainly don’t lead our lives that way. Humanity, as a rule, does not pretend to be anything other than the Center of Everything! But it could be that we inhabit a Cosmos with other intelligences, some perhaps vastly greater than our own, some perhaps implacable and as unaware of us as we might be of ants or bacteria. Such musings are disquieting because they challenge the central tenet of our perceived existence as the premiere lifeform, on planet Earth or anywhere else.

The question of whether the Cosmos harbors life elsewhere is a compelling one from the perspective of our psychology, but also because there is an apparent conflict between two eminently reasonably scientific viewpoints. The first of these viewpoints is the so called “Principle of Mediocrity.” This is the no-holds barred manifestation of the Copernican Principle — there is nothing special about the Earth. The Cosmos seems to be filled with planets (the latest count, as of today, 9 Dec 2013 is 1051 known planets (visit the Exoplanet Encyclopedia Catalog), with some 3000 candidates from the Kepler mission. Our deepest probes of the Cosmos (the Hubble Extreme Deep Field) suggests there could be as many as 600 billion galaxies. If each galaxy has 300 billion stars, and every star has at least 1 planet (probably more) then there are a staggering number of possible worlds on which life could have arose. There is nothing special about Earth, so if life arose here, there should be no impediment to life arising on any of the trillions and trillions of other worlds that fill the Cosmos.

![The Hubble Extreme Deep Field (XDF). [Credit: NASA; ESA; G. Illingworth, D. Magee, and P. Oesch, University of California, Santa Cruz; R. Bouwens, Leiden University; and the HUDF09 Team]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/hst_xdf.jpg?w=500&h=436)

The Hubble Extreme Deep Field (XDF). [Credit: NASA; ESA; G. Illingworth, D. Magee, and P. Oesch, University of California, Santa Cruz; R. Bouwens, Leiden University; and the HUDF09 Team]

The opposing viewpoint is something called “The Fermi Paradox.” It was originally proposed by Enrico Fermi, and can succinctly be summarized as, “Where are they?” What Fermi wondered was why has the Earth, or any world in the solar system, not been visited by self-replicating robotic explorers of some distant alien race? His point was that if we really want to explore the galaxy, the most efficient way to do that would be to send a robotic probe out to the nearest star. It won’t get there in a human lifetime, but it will get there in a time substantially shorter than the age of the galaxy. When the robot gets to a star system, it pokes around a bit, then builds 10 copies of itself using the natural resources it can find, and sends those copies out to the next 10 closest stars. If every robot successfully makes 10 copies of itself, it only takes 11 replication cycles before there is 1 robot for every star in the galaxy. But really, why would they stop there? They would just keep replicating until there are a whole lot of robots in the galaxy. But we haven’t seen one yet! Why not? One’s immediate gut reaction might be to think, “Well humans are just the first species to have such a crazy idea. The galaxy is not full of self-replicating robots because we haven’t built them yet!” But if we apply the Copernican Principle to Earth and humanity in particular, there is no reason to believe we are the first instantiation of intelligent life; some civilization should have preceeded us, and built the fleet of galaxy filling robots. But there are no robots, and the chance that we are the first civilization in the entire galaxy is vanishingly small. The fact that there are no robots means that we are alone in the Cosmos.

The opposing viewpoint is something called “The Fermi Paradox.” It was originally proposed by Enrico Fermi, and can succinctly be summarized as, “Where are they?” What Fermi wondered was why has the Earth, or any world in the solar system, not been visited by self-replicating robotic explorers of some distant alien race? His point was that if we really want to explore the galaxy, the most efficient way to do that would be to send a robotic probe out to the nearest star. It won’t get there in a human lifetime, but it will get there in a time substantially shorter than the age of the galaxy. When the robot gets to a star system, it pokes around a bit, then builds 10 copies of itself using the natural resources it can find, and sends those copies out to the next 10 closest stars. If every robot successfully makes 10 copies of itself, it only takes 11 replication cycles before there is 1 robot for every star in the galaxy. But really, why would they stop there? They would just keep replicating until there are a whole lot of robots in the galaxy. But we haven’t seen one yet! Why not? One’s immediate gut reaction might be to think, “Well humans are just the first species to have such a crazy idea. The galaxy is not full of self-replicating robots because we haven’t built them yet!” But if we apply the Copernican Principle to Earth and humanity in particular, there is no reason to believe we are the first instantiation of intelligent life; some civilization should have preceeded us, and built the fleet of galaxy filling robots. But there are no robots, and the chance that we are the first civilization in the entire galaxy is vanishingly small. The fact that there are no robots means that we are alone in the Cosmos.

![Why has our solar system not been visited by alien robots, sailing through to see what the galaxy is full of? This is the central tenet of the Fermi Paradox. [Model by S. Larson]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/lyranintruder.jpg?w=500&h=335)

Why has our solar system not been visited by alien robots, sailing through to see what the galaxy is full of? This is the central tenet of the Fermi Paradox. [Model by S. Larson]

![The dinosaurs haven't (didn't?) go exploring the galaxy. [Image from Captain Raptor and the Moon Mystery, by O'Malley and O'Brien]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/captainraptorobrien.jpg?w=215&h=300)

The dinosaurs haven’t gone (didn’t go?) exploring the galaxy. [Image from Captain Raptor and the Moon Mystery, by O’Malley and O’Brien]

But we don’t even have to think about lifeforms long gone. Even among our own species, entire civilizations have utterly vanished from the world. Five thousand years ago, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was comprised of 5 million persons, fully 10% of the entire world population at that time. It stretched all along the Indus River valley, in what is today the borderlands between modern India, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The preeminent civilization of the era, the IVC developed the first system of weights and measures; quantitative measure is the foundation of all technology and science. But they did not colonize the galaxy. The civilization survived for almost two millennia, until the cities were mysteriously abandoned and the civilization collapsed, never having once cast their voice out into the Cosmos. Before they had the ability to build a robot, drought and shifting economics with other, nearby civilizations destroyed the greatest civilization the world had known to that time.

If I were to take these two examples at face value, and use my imagination to extrapolate to other worlds, I might imagine that life is common throughout the Universe, but perhaps it is far too fragile a form of matter to survive. Perhaps it is always obliterated, by the abusive hand of the Cosmos or through ignorance and self-destruction. Obliterated before it can send its seed, robotic messengers, out into the Cosmos. That would be a depressing thought, with terrifying implications for our future on this world. But it is not inconceivable (even knowing what that word means); even in my lifetime, the spectre of the destruction of our world has constantly loomed, though it has been an evolving chorus of spectres, each sharing the lead. As a child growing up in the 1980s, the possibility of nuclear annihilation was real and forefront in our minds, even as children. The threat is perhaps no less real today, but the end of the Cold War has reduced the threat in people’s imaginations. Today, the fragility of our climate and environment plays a more prominent role in considerations of what our future may be. Now, as in The Cold War, the conversation is driven by ideology and arguments built around emotional viewpoints rather than scientific considerations. It is not clear we will survive to build a robot army that will explore the galaxy.

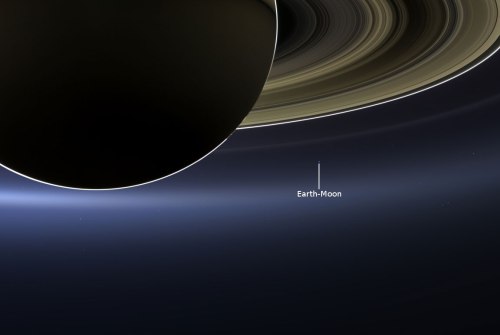

Another possibility is that maybe it is just too hard to find other life. Maybe it is out there, but detecting it is far more difficult than finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. We are not even sure if there is life elsewhere in the solar system, and we live here! What would an alien robot sailing into the solar system find? There are almost 100 known worlds in the solar system that are at least large enough to be round (say larger than 200km; list at Wikipedia). Would a robot explore all of them, or simply gaze from afar? Consider what the Earth looks like from beyond Saturn. Can you tell there is life here? Look at the Earth from the Moon. Can you tell there is life here, especially compared to a picture of Titan from roughly the same distance? What if the probe never came in this close, landing on the first world it encountered, say Neptune’s enigmatic moon Nereid?

The Earth (L) and Titan (R), each viewed by a spacecraft from roughly the same distance. Can you tell if either harbors life?

Despite all the difficulties, real and imagined, of searching for life elsewhere, we continue to do it, both by sifting the surfaces of worlds near Earth, as well as plumbing the depths of interstellar space looking for messages from other beings. The idea of there being life elsewhere is one that is hard to let go of, because the alternative is far too depressing — that we truly are alone. It is a staggering thought, which we are constantly reminded of.

There is a very famous picture of Earth, taken by Michael Collins during the Apollo 11 flight. As the ascent stage of the Lunar Module Eagle returned to dock with Collins aboard the Columbia in lunar orbit, he snapped a picture showing the Eagle (containing Aldrin and Amrstrong) hanging in front of the magnificent desolation of the Moon, with the partially illuminated Earth in the background. Collins later remarked, “I remember most vividly the picture of the lunar horizon and then the LEM ascent stage in the foreground with these two guys in it, and then the Earth popping up at that instant… You’ve got 3 billion people over there, two people here and that’s it.”

![A picture from Apollo 11 of every human being, alive or dead, except for Michael Collins (the photographer). [NASA Image AS11-44-6642]](https://writescience.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/as11-44-6642hr.jpg?w=500&h=497)

A picture from Apollo 11 of every human being, alive or dead, except for Michael Collins (the photographer). [NASA Image AS11-44-6642]

————————————

This post is part of an ongoing series, celebrating the forthcoming science series, Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey by revisiting the themes of Carl Sagan’s classic series, Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. The introductory post of the series, with links to all other posts may be found here: http://wp.me/p19G0g-dE