by Shane L. Larson

Humans have looked at the sky for as long as we have inhabited our small, planetary home. For 40,000 generations we have basked in the warmth of our mother the Sun, watched the Moon hurtle across the sky in an ever-changing succession of phases, and fallen asleep as the stars slowly wheeled overhead in their familiar and comforting constellations.

The familiar shape of Orion, with it’s distinct three belt stars, graces the winter skies in the Northern Hemisphere, as it has for all of recorded human history. [Image: M. Larson (iphone!)]

Comet NEOWSIE (C/2020 F3) graced the skies of Earth unexpectedly in the summer of 2020, during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Comets are one example of rare, transitory experiences humans can have with astronomy. [Image: S. Larson]

Any of these events are dramatic enough to have caused consternation in the course of human history, particularly in the days before humans had begun to dissect the patterns of Nature and use that knowledge to better understand our place and purpose in the Cosmos.

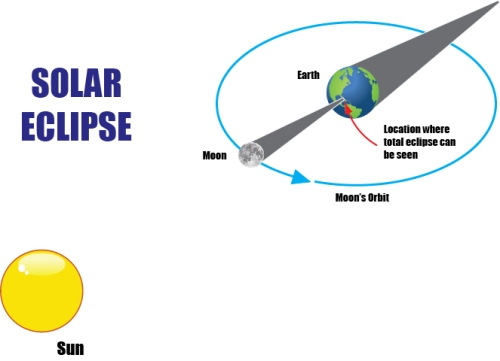

But you and I live in the future. Many before us, both before the birth of modern science and after, have learned the patterns of the sky to such precision that we can predict when the Moon will spin into the line of sight between us and the Sun, and shed a narrow band of shadow on the Earth — a solar eclipse.

A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Earth and Sun. The Moon’s shadow races across the surface of the Earth, blotting out the Sun for those who stand under the racing shadow. [Illustration by S. Larson]

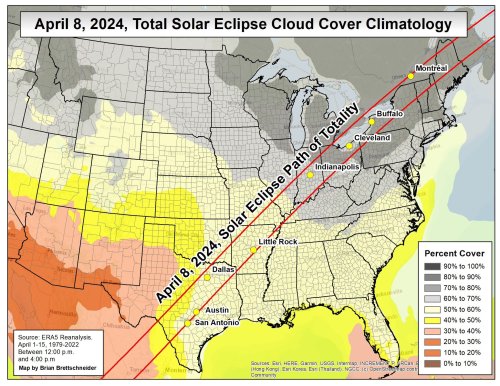

The path of the 8 April 2024 total solar eclipse, moving from the southwest to the northeast over North America. The centerline is marked in red; everyone in the grey band was within the path of totality. [Illustration: S. Larson]

The April 2024 eclipse was a remarkable opportunity for many of us who had asked that question. We could travel to the centerline pretty easily, and the duration of the eclipse was going to be longer than in 2017 — almost four and a half minutes, longer than the two minutes and 27 seconds from 2017. It doesn’t sound like much, but some deep part of our soul knows that longer matters.

That’s because standing in the shadow of the Moon, your mind knows something remarkable is happening, but it is far outside your everyday experience. It is difficult to grasp and hold on to and put into words. You have a lifetime of experience with the Sun — it is steady and reliable and is the same every time you see it. You never see it do something unusual, and your brain knows it. When the Sun disappears, and is replaced by an inky spot of darkness in the sky, you feel it deep down in your soul, and you want to hold on to that memory and feeling — it is precious.

A message from a friend of mine about the experience of standing in the utter darkness of totality during a solar eclipse. [Shown with permission]

But from where?

A site was selected based on historical weather averages. April is springtime in North America. Along wide swaths of the eclipse track that means turbulent weather, spring rains, occasional snows, and cloudy days as Spring tries to assert herself over Winter. For many, this is a once-in-a-lifetime event, so you play the odds. We, like many others, descended on Texas.

We settled on an RV park in the Texas hill country, west of San Antonio, on the banks of the Rio Frio just outside Garner State Park. If you were to pick an awesome site for the eclipse, this was the one. Right along the centerline.

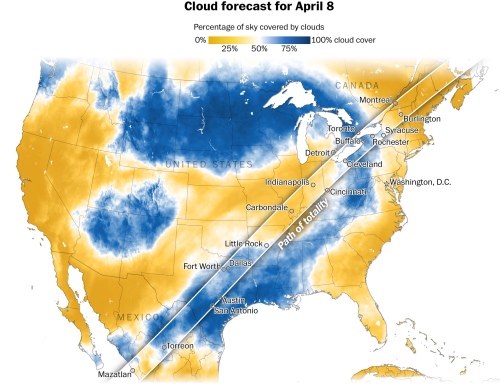

We converged on Saturday, two days before the eclipse, and the forecast was looking grim. Predictions for Eclipse Day on Monday were for 90% clouds, possible rain. Quite against all odds, the northern reaches of the eclipse track, historically cloudy in April, were predicting clear skies!

The agony of statistics!

There was a lot of hand-wringing around the firepit that evening, and long into the next day. What should we do? Should we stay put? Should we try and drive to clear skies? It was predicted only 50% cloudy three hours north — were those odds we liked? It was predicted only 10% cloudy nine hours north in Arkansas? Did we want to do 18 hours on the road (there and back)? What if we got caught in traffic and missed everything?

In the end, we decided to stay put. The magic of the moment was being together, and there was still an experience to be had. Even on a cloudy day, it was still going to get unnaturally dark. Maybe we’d get lucky, and maybe we wouldn’t.

Eclipse day dawned cloudy, as predicted. But Nature is a tease. The clouds were layered, and moving in different directions, and every now and then there was a fabulously clear blue spot, sometimes in front of the Sun — shadows would sharpen and we could feel the warmth on our faces, tantalizing moments of hope.

We had an eclipse talk before the event, to answer questions and help everyone feel like they were prepared. [Image: M. Mesel]

Then we all dragged our camping chairs to a wide grassy spot, and waited. The clouds were thick, but there were gaps that dashed across the sky, and moments where we could make the Sun out through the clouds, and other times it stood in the clear sky. Eclipse glasses pressed tightly to our eyes, we could see the Moon had started the eclipse run and was dutifully eating more and more out of the right side of the Sun.

First we could see just a little tentative nibble, and then a cloud would dash in front and obscure the view. But just a tiny bit later, the Sun would emerge again, and joyous cries of amazement would rise up from the sea of chairs as people witnessed the Sun slowly disappear.

Our views of the ongoing eclipse through eclipse glasses (left) and through the cloud layer (right). [Images: S. Larson]

We could feel the chill on our skin. Was it the ever fading light from the Sun, now obscured? Or was it the cold embrace of weather carried on our nemesis, The Cloud?

Totality was approaching, not a break to be seen. Dutifully linked to the digital world, we had GPS times on our phones, and precise knowledge of when Totality should occur, now on the far side of The Cloud. About 20 seconds before Totality, a swelling countdown rolled across the sea of people…20 – 19 – 18 – 17 – 16 – 15 – 14 – 13 – 12 – 11 – 10 – 9 – 8 – 7 – 6 – 5 – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1 – 0!

Right on cue, the skies descended to darkness. What was moments before a cloudy day illuminated by dim filtered sunlight, plunged into darkness. People erupted in applause and cries of joy.

Totality descended on us, right on schedule. Dark as night, but it swept over us in mere seconds. [Image: S. Larson]

The automatic streetlight at the entrance to the RV park came on. The birds got quiet. Bats started flitting overhead. The humans were still taking pictures. We craned our heads around, and could see that near the horizons, it was still light — realms outside totality, where the light still fell. But where we were, it was dark.

For 4 minutes and 28 seconds, we were in the Shadow of the Moon.

We stood in totality, and could not see the Sun nor the gossamer aura of its corona. But still we stood in the darkness in wonder. [Image: S. Larson]

And then, it was over as quickly as it had started. The light rose, and we were once again sitting in a grassy patch on a cloudy spring day, the soft light of the Sun filtered by clouds above. Except we were different. For a long while, we stayed put. Comparing experiences, taking selfies, laughing, and sharing the joy.

Later that night, after normal darkness fell, we sat in a great circle in the middle of the camp, and engaged in another time-honored human tradition of sharing songs and music. Songs of the sky and moonshadows, songs of sharing and family, and songs of learning and travelling home. Picked out on the strings of a guitar, with some voices well-trained and other voices simply happy to be together, we bonded just a little bit more to ensure that we each remembered how special that day had been.For some of us, there will be other eclipses. Perhaps with clouds, perhaps without. But for all of us, there were four and half ephemeral minutes of darkness that we shared, on the middle of a cloudy day in southern Texas.

Thank you, Shane. Love this blog and getting to hang with you, and your talk was wonderful and informative.

It was great fun all around — we’ll do it again sometime! 🙂