by Shane L. Larson

One of the great pleasures of my life is going to scientific conferences. I love sitting through talks, listening to my colleagues weave tales of things I’ve never thought about before. I find something deeply relaxing about simply letting new information seep into my brain and connect to things one might never have expected. It makes my life and daydreams interesting.

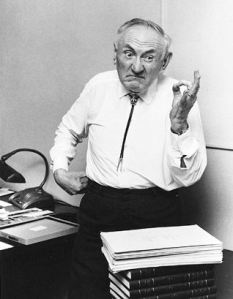

I was sitting at a meeting in Denver recently, listening to one of my colleagues spin a tale I’ve heard before, about the dark matter in the Cosmos. The idea that the Universe is not entirely made of the same stuff as you and I was pioneered in the 1930s by Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky, based on a famous observation of the motion in a distant cluster of galaxies known as the Coma Cluster. Zwicky showed that if you count up all the stuff you could see in your telescope and compared it to how much stuff you need to make the galaxies move, there was some matter that was missing, or dark! This is a famous and important result, and my colleague did what we all do when we tell this tale: he put up a picture of Zwicky. More often than not, we all use the picture shown to the left!

Which got me to wondering — if Zwicky were still with us today (sadly, he has gone back to the Cosmos in 1974) and I were to drop him an email asking for a picture of him to show in a talk, what would he send me?

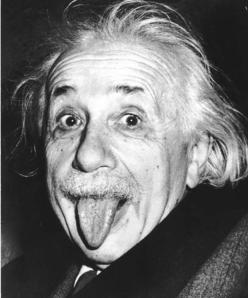

There are other examples of funny scientist pictures that are commonly used. Perhaps the most famous is of Albert “Big Al” Einstein, sticking out his tongue. The picture was taken by a UPI reporter on Einstein’s 72nd birthday, and was a favorite of Einstein’s. It is arguably one of the most popular images of Einstein and is used in many venues, especially when talking about complicated physical concepts that derive from Einstein’s work. I use it in two different instances. The first is when I’m trying to convince people that scientists aren’t completely serious people — we like to have fun and goof off; if Einstein did it, so can we! We’re people too! The second is when I’m talking to people about dark energy — a completely unknown physical effect that appears to comprise almost 70 percent of the Universe. Einstein’s famous “blunder,” known as the Cosmological Constant, is a leading candidate for explaining the dark energy. I like to think that if I could call Einstein up on the phone and tell him we were going to use his greatest blunder to explain the greatest mystery in physics today, he might think I was pulling his leg and blow a big raspberry over the phone, like he appears to be doing in this picture!

Not all of my colleagues use pictures when they talk science; not all of them regale us with historical tales of the subject they are outlining. But I always do because to me, the context of the story is as important as the scientific result itself. Science is a uniquely human endeavour — no other species that we know of studies the world like we do. Science, like art, is an intense expression of our innermost creativity and imagination. As such, it is important to me to put a human face on all the great mysteries we have unravelled, and on all the puzzles we are still trying to find answers to.

Consider Jane Goodall, widely known for her decades long research on the Gombe chimpanzees in Tanzania. I would love to be a collaborator with Goodall, so I could ping her for a picture to use. What picture would she choose? There are thousands of pictures of Goodall and the Gombe chimpanzees, many quite famous, but the most striking to me has always been this one by Michael Nichols of National Geographic. It captures so eloquently the interspecies interaction which has always been the hallmark of Goodall’s work. While the unconventional methods Goodall used in characterizing her work has often garnered criticism centered around the anthropomorphization of the chimpanzees, it is precisely the idea that we are closely related to these other Earthlings that makes Goodall and her work so compelling to the rest of us. All the subtle mix of wonder and mystery at this deep connection with our cousins, the great apes, is captured for me in this single image.

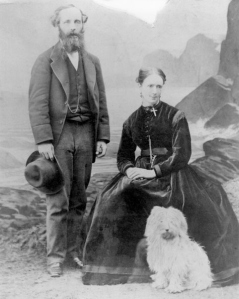

The existence of funny or striking images is largely due to the development and commercialization of film. Today especially, pictures are cheap and easy — goofing off for the camera is a worldwide pastime! But before cameras and photography became common, photographic pictures were posed and planned. As a result, as one looks back in time, it seems to me that we often simply have the image of famous scientists, and little of their personality. But I still show their pictures.

This is one of my favorite pictures of James Clerk Maxwell, though it is not one you often see. It shows the iconic Maxwell that is so well known to physicists, in his mid-life, with his signature bushy beard, together with his wife Katherine. Maxwell was a phenomenal physicist, contributing to many areas including color photography and thermodynamics. What he is most well known for, however, is the combination of electricity and magnetism into one, unified description of Nature now called “electromagnetism.” It was the first time humans had ever come to the realization that there was some deep unification possible in the Laws of Nature, and set the stage for fundamental physics research that continues to this day; the quest to find the Higgs boson is the distant descendant of Maxwell’s original epiphany about unification. What I love most about this picture is that Maxwell had a fuzzy sheep dog! If Maxwell had posted this picture to Instagram, I’m sure I’d shoot him a text right away saying, “LOL Jim. What’s the dog’s name?”

Portrait of a man in red chalk. Possibly a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci.

Beyond the horizon in time when photography was invented, our memories of distant ancestors and figures is reduced to art. It is no secret that I harbor a deep romanticism for Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps the greatest polymath known in history. It is a fond daydream of mine to imagine sitting on a hillside somewhere with Leonardo, sketching in my Moleskine next to the great master as we engage in idle chit-chat, speculating on the awesome machinery of Nature and how we humans might tap into that machinery and be more than we think ourselves to be — to fly, or traverse the wide oceans, or to build a violin whose sound would make the masses weep with joy to hear the sound of it. There are many portraits of Leonardo, but the one I carry in my mind is one that is thought to be a self-portrait (though this is debated), the famed “Portrait of a man in red chalk.” If it is Leonardo, it shows him late in his life. I’m most captivated by the eyes in this portrait — deep, hidden under bushy eyebrows, the corners lined with wrinkles that I imagine must be derived from a life filled with laughter and delight at all the world has to offer. Too much to read into fading lines of chalk sketched five hundred years ago? Perhaps, but it keeps me putting my pen to paper every day, spilling out crazy ideas and imaginings about the world. What would Leonardo do?

Because I do place great stock in the human story of science, my passion for showing pictures of scientists doesn’t end with historical retrospectives. Most of my colleagues have at some point in our collaborations been asked for a picture, so I can show the world the people I work with. They are all brilliant, unique, imaginative scientific minds. As you might imagine, their pictures reflect their inner brilliance. I show their pictures when I give talks to bring those human dimensions to our work, because I am proud to call them friends and colleagues.

Here is my academic family, my research group from my last year at Utah State University. They are, each of them, singularly brilliant and talented. Every one of them is just beginning to write their stories. I have no doubt that if they come visit me in the old scientists’ home when I’m 107, they’ll bring pictures of their adventures and tell me tales of the paths they walked in the world, no matter what they might be. We’ll pull out this old picture, and laugh at how young we all were back then, and how quaint “digital pictures” were back when that technology was new-fangled.

Someday, one of my students, or one of you, will need a picture of me for something. When you do, do me a favor — no serious pictures. If I’m lucky, I’ll have some odd little picture that is so awesome everyone will use it, just like the picture of Fritz Zwicky. Until then, I’ll leave you with one my favorites — my selfie. Not as compelling as Goodall’s picture, nor as elegant as Leonardo’s portrait, but maybe as serious as Einstein’s. 🙂