by Shane L. Larson

On a forgotten autumn day long ago, I sat amidst hundreds of strangers in the far-away ballroom of a convention center in Oregon. I was younger than I am now, younger than most of those who were sitting around me. Yet somehow, I had been chosen. I had been waiting. I had rolled that singular moment of time around in my head, over and over again. Out of all the hundreds of hands in the air, mine was chosen, and I stood to ask a question.

My palms were sweaty, my heart raced. I took the microphone, and thankfully didn’t drop it. In those days, I had yet to ever speak in front of more than a small group of my friends in class, but here I was, and damnit I was going to ask my question! Five hundred pairs of eyes stared right at me, and from the stage, the cool gaze of our guest, encouraging and expectant. I’m sure I squeaked; I must have squeaked. But out came my question: “What is the responsibility of science fiction to bring plausible visions of the future to us?”

The person I had directed my inquiry to was William Shatner, who had been regaling the crowd of Trekkers with tales of life in the Big Chair, and answering questions about how to properly act out a Star Trek Fight Scene, whether he really thought Kirk should have let the Gorn survive, and whether Spock ever just burst out laughing on set. And then I stood up to ask my question.

The person I had directed my inquiry to was William Shatner, who had been regaling the crowd of Trekkers with tales of life in the Big Chair, and answering questions about how to properly act out a Star Trek Fight Scene, whether he really thought Kirk should have let the Gorn survive, and whether Spock ever just burst out laughing on set. And then I stood up to ask my question.

“What is the responsibility of science fiction to bring plausible visions of the future to us?”

For all the ribbing that Shatner takes for being Shatner, I think he responded in a way that might surprise many people. He smiled, he didn’t laugh. He looked me straight in the eye and told me this: “Science fiction is like all art — it is a medium for telling stories about our humanity. Visions of the future are just stories about us.” It was a brilliant and thoughtful answer, and I’ve always remembered it.

Now, many years later, I practice science. I still watch a lot of Star Trek, and I absorb a lot of science fiction, and every time I reach the end of a novel or movie, I know Bill was right — the best stories are the ones that use the future as a backdrop to tell human stories.

Larry Yando as the titular character in the Chicago Shakespeare Theatre’s 2014 production of King Lear.

That’s a very interesting thought when I drape it across the tapestry of art, literature, and theatre. All forms of art are explorations of what it means to be human, attempts to understand on a very deep level who we are. Just this past weekend, sitting in the darkened theatre of the Chicago Shakespeare Theatre, I was bludgeoned by that simple fact once again watching King Lear. Though the story is set long ago, and though the language is not all together our own, we sat there enraptured. The tale is full of intrigue and betrayal, but at the core is the King. Watching the play reflected the dark pools of shadowed eyes, you could see an audience tearfully and painfully aware that the tragedy unfolding from the King’s descent into madness was an all too relevant tale for those of us who have suffered the loss of elderly friends and relatives to the ravages of age. Our humanity was laid out, naked and bare on the stage, in a tale written more than 400 years ago. The core message is as relevant and pertinent today as it was when the Bard penned it those long centuries ago.

The exploration of the nature of the human spirit has long been the purview of all forms of art, especially performance. The whole point in acting out stories is to tell stories about people. Even when the characters aren’t people, they still talk and act like people, anthropomorphized by their actions, their thoughts, and their words in the tapestry of story on the stage or screen. And so I suppose it should not have surprised me that Shatner did not think of tales from the far future any differently — the stories are still stories about us. They still are stories about our triumphs, our tragedies, our frailties, and our fallacies.

But that younger version of myself carried a particular conceit — I wasn’t clear about it then, but I still harbor it today: I fundamentally believe that art and science have exactly the same purpose — to discover the stories of who we are, and what our place in the Cosmos is. The truth of this is hidden in every science book and every textbook you have ever picked up and thumbed through. How? Very seldom is science explained without the context, the wrapper, of the human story around it.

Newton witnessed the falling of an apple when visiting his mother’s farm, inspiring him to think about gravity. It is almost certainly apocryphal that it hit him on the head! But art gives the story a certain reality!

When we are first taught about the Universal Law of Gravitation, very seldom are you simply told the equation that relates mass and distance to gravitational force. Instead, we cast our minds back to a late summer day in the 17th Century. On a warm evening after dinner, Isaac Newton was sitting in his mother’s garden, on her farm in Lincolnshire and was witness to an ordinary event: an apple falling to the ground. A simple, ordinary event, part of a tree’s ever-repeating cycle of reproduction. But witnessing the event sparked a thought in Newton’s mind that ultimately blossomed into the first modern Law of Nature. The tale inspires a deep sense of awe in us. How many everyday events have we witnessed, but never taken the time to heed? How many secrets of Nature have passed us by, because we never connected the dots the Cosmos so patiently lays out before us?

When we first learn about the discovery of radioactivity, very seldom are we only told the mass of polonium and the half-life of uranium. Instead, we relive the discovery of radioactive decay alongside Marie Curie, who unaware of the dangers of radiation, handled samples with her bare hands and carried test tubes full of the stuff around in her pockets. We know that she developed the first mobile x-ray units, used in World War I, a brilliant realization of mobile medical technology at the dawn of our modern age. But we also know that Curie perished from aplastic anemia, brought on by radiation exposure. Today, her notebooks and her belongings are still radioactive and unsafe to be around for long periods of time. Curie’s death is a tragic tale of how the road to discovery is fraught with unknown dangers. While we mourn her loss we celebrate also the wonder that our species has such brilliant minds as Marie Skłodowska-Curie, the only person ever to win TWO Nobel Prizes in different sciences (Chemistry and Physics)

When we learn about antibiotics, seldom do we begin in the lab with petri dishes full of agar. Instead, we are taught the value of serendipity through the tale of Alexander Fleming. In late September of 1928 he returned to the laboratory to find that he had accidentally left a bacterial culture plate uncovered and it had developed a mold growth. You can imagine a visceral emotional reaction — anger! Another days-long experiment ruined! By sheer carelessness! It happens to all of us every day when we burn a carefully prepared dinner, or break a favorite coffee mug, or accidentally drop a smartphone down an elevator shaft. But through the haze of aggravation, Fleming noticed something subtle and peculiar — there were no bacterial growths in the small halo around the mold. The mold, known as Penicillium rubens, could stop a bacteria in its tracks. That single moment of clarity launched the development of antibiotics, so crucial in modern medical care. What world would we inhabit today, if Fleming had thrown that petri dish away in disgust, without a second glance? Surely a tragedy of world-girdling proportions.

All of these stories illustrate a subtle but singular truth about our species: we are different from all the other lifeforms on our planet. Not in sciencey ways — we have the same biochemical machinery as sunflowers, opossums and earthworms — but in less tangible abstract ways. What separates us from all the other plants and animals is the way we respond to the neurological signals from our brains. Our brains are wired to do two interesting things: they imagine and they create. The truth is we don’t fully understand how our brains do these things, or why there is an apparent biological imperative to do either. But the result of those combined traits is an insatiable curiosity to know and understand ourselves and the world around us, and an uncontrollable urge to express what we discover.

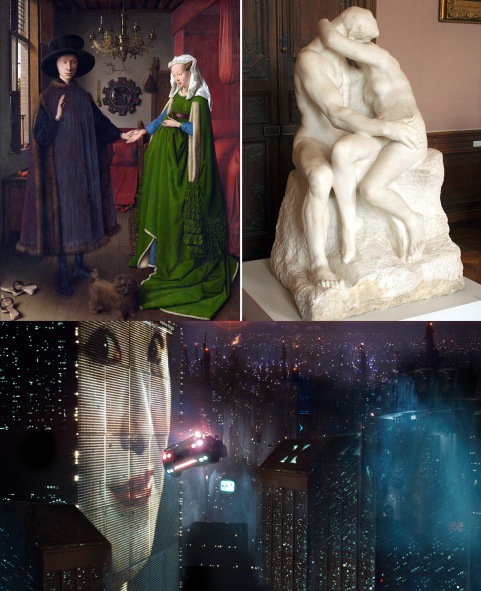

Sometimes those expressions burst out of us in moments of creation that lead to lightbulbs, intermittent windshield wipers, kidney dialysis machines, and iPads. Sometimes those same expressions burst out of us in moments of creation that lead to Jean van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, or Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss, or Steve Martin’s “Picasso at the Lapine Agile,” or Ridley Scott’s desolate future in “Blade Runner.”

(Top L) Jean van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait; (Top R) Rodin’s The Kiss; (Bottom) The urban dystopia of the future in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

Art is like science. Imagination expressed through long hours of practice, many instances of trial and error, and moments of elation that punctuate the long drudgery of trying to create something new. Science is like art. Trying to understand the world by constantly bringing some new creative approach to the lab bench in an attempt to do something no one else has ever done before.

Both science and art are acts of creation with one express goal: to tell our stories. Both require deep reservoirs of creativity. Both require vast amounts of imagination. Both require great risks to be taken. But in the end, the scientist/artist creates something new that changes who we are and how we fit into the world. And wrapped all around them are all-together human tales of the struggles encountered along the road to discovery.

It is not entirely the way we are taught to think about scientists and artists. Isaac Asimov famously noted this in his 1983 book Roving Mind: “How often people speak of art and science as though they were two entirely different things, with no interconnection. An artist is emotional, they think, and uses only his intuition; he sees all at once and has no need of reason. A scientist is cold, they think, and uses only his reason; he argues carefully step by step, and needs no imagination. That is all wrong. The true artist is quite rational as well as imaginative and knows what he is doing; if he does not, his art suffers. The true scientist is quite imaginative as well as rational, and sometimes leaps to solutions where reason can follow only slowly; if he does not, his science suffers.” An interesting thought to ruminate on the next time you are preparing DNA samples or soldering stained glass mosaics.

I have to go now. The crew of the Enterprise have some moments of humanity to show me. See you in an hour.